Jan Bartek – MessageToEagl.com – The Judean Desert is a unique time capsule for archeologists: thanks to the arid conditions that prevail there, its caves preserve ancient artifacts made of organic materials, which would have otherwise decayed and disappeared under normal conditions.

An example of a cave where fascinating finds were uncovered is the Nahal Hemar Cave. The cave was discovered in 1983 by David Alon and Eid Al-Tori and was investigated by David Alon and Ofer Bar-Yosef from the Israel Department of Antiquities.

Credit: Israel Antiquities Authority

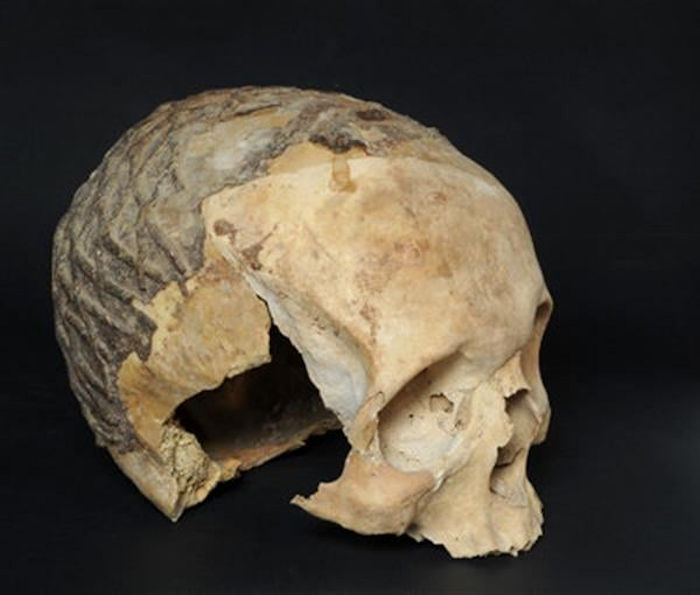

Among various treasures unearthed in the cave, human bones were also found, including skulls dating to the 7th millennium B.C.

Unusual remnants of asphalt were found smeared on six skulls, and the excellent state of preservation of three of them allows us to study the phenomenon:

It seems that a thin layer of asphalt was smeared on the back of the skull. Then, thin threads of asphalt were prepared by rolling the material between the hands, and these were placed on the first layer to create the appearance of a net – or even a hat, as can be seen in the picture.

Credit: Israel Antiquities Authority

A study of similar findings revealed that the treatment and designs on the skulls of older people were common in the 7th millennium BCE: The origin of the custom probably lies in the Natufian culture.

See Also: More Archaeology News

Researchers believe that the custom originated in ancestor worship, possibly in order to strengthen the sense of belonging to an extended family unit. In agricultural societies, where population density steadily increased, family affiliation largely determined every individual’s place and economic status in society. Therefore, the preservation and marking of the ancestral skulls and objects belonging to the ‘founding generation’ constituted a sign of belonging and status.

Other objects associated with this custom are masks – two were found in the same cave in Nahal Hemar, and they have also been discovered in other places in the country. Plastered skulls and masks dating to this early period point to a broad social phenomenon, reflecting the local religious culture.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer