Unique Over 1,000-Year-Old “Telephone” Invented By A Lost Forgotten Civilization With No Written Language

MessageToEagle.com – Our modern society is proud of recent scientific advances and incredible technological breakthroughs.

We have undoubtedly come a long way, and we hear almost every day of new effective high-tech products that are meant to improve our lives.

Yet, every now and then we come across some ancient, forgotten artifacts that make us stop and re-evaluate the world we are living in.

Are we really so smart? Maybe we don’t give the ancients the credit they deserve? Perhaps some of our inventions are nothing but re-inventions of things that existed in the distant past.

The telephone was officially invented in the 1870’s when two inventors Elisha Gray and Alexander Graham Bell both independently designed devices that could transmit speech electrically (the telephone).

Both rushed their respective designs to the patent office within hours of each other. However, Alexander Graham Bell patented his telephone first. Gray and Bell entered into a famous legal battle over the invention of the telephone, which Bell eventually won.

Most people are familiar with the story of Bell and his invented telephone.

What many might not know is that about 1,200-1,400 yeas ago a simple society with no written language used a device that was similar to our telephone.

In the National Museum of the American Indian storage facility in Suitland, Maryland, there is a precious object that could be the earliest known example of telephone technology in the Western Hemisphere.

“This is unique. Only one was ever discovered. It comes from the consciousness of an indigenous society with no written language,” NMAI curator Ramiro Matos, an anthropologist and archaeologist who specializes in the study of the central Andes says.

“We’ll never know the trial and error that went into its creation.

The marvel of acoustic engineering-cunningly constructed of two resin-coated gourd receivers, each three-and-one-half inches long; stretched-hide membranes stitched around the bases of the receivers; and cotton-twine cord extending 75 feet when pulled taut-arose out of the Chimu empire at its height.

The dazzlingly innovative culture was centered in the Río Moche Valley in northern Peru, wedged between the Pacific Ocean and the western Andes, “Smithsonian magazine reports.

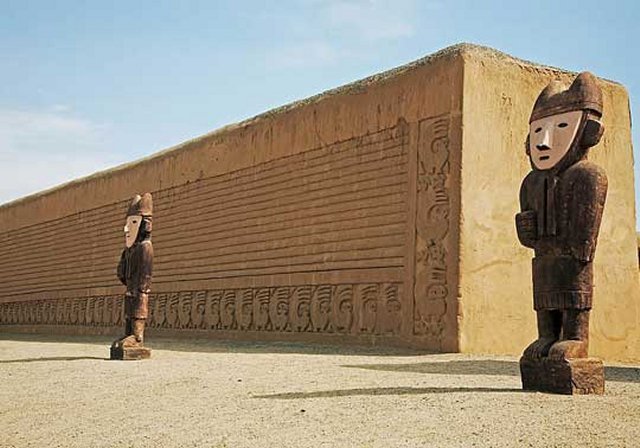

The Chimu Empire’s capital was at Chan Chan in the Moche valley. It was an impressive ancient city.

Chan Chan was the largest earthen architecture city in pre-Columbian America. The remains of this vast city reflect in their layout a strict political and social strategy, emphasized by their division into nine ‘citadels’ or ‘palaces’ forming independent units.

Chan Chan Archaeological Zone is today on Unesco’s list.

The Outstanding Universal Value of Chan Chan resides in the extensive, hierarchically planned remains of this huge city, including remnants of the industrial, agricultural and water management systems that sustained it.

The monumental zone of around six square kilometres in the centre of the once twenty square kilometre city, comprises nine large rectangular complexes (‘citadels’ or ‘palaces’) delineated by high thick earthen walls. Within these units, buildings including temples, dwellings, storehouses are arranged around open spaces, together with reservoirs, and funeral platforms.

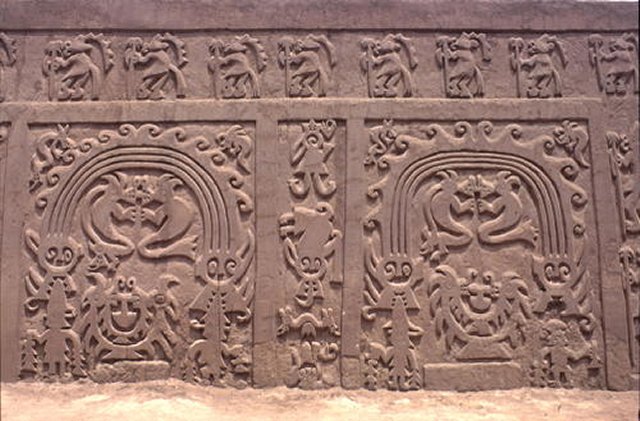

The earthen walls of the buildings were often decorated with friezes representing abstract motifs, and anthropomorphical and zoomorphical subjects.

Around these nine complexes were thirty two semi monumental compounds and four production sectors for activities such as weaving wood and metal working. Extensive agricultural areas and a remnant irrigation system have been found further to the north, east and west of the city.

Based on what is known, in 1470, the Chimu were conquered by the Incas under Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui and his son Topa Inca Yupanqui.

The Chimu were a skillful, inventive people and they were the first true engineering society in the New World.

The Chimu telephone artifact or as it usually called the “NMAI telephone” has a mysterious past.

“Somehow-no one knows under what circumstances-it came into the hands of a Prussian aristocrat, Baron Walram V. Von Schoeler. A shadowy Indiana Jones-type adventurer, Von Schoeler began excavating in Peru during the 1930s. He developed the “digging bug,” as he told the New York Times in 1937, at the age of 6, when he stumbled across evidence of a prehistoric village on the grounds of his father’s castle in Germany. Von Schoeler himself may have unearthed the gourd telephone. By the 1940s, he had settled in New York City and amassed extensive holdings of South American ethnographic objects, eventually dispersing his collections to museums around the United States.”

The Chimu were organized as “a top-down society and it believed that the NMAI telephone was used by the elite, perhaps only the priests.

The city’s ancient architecture reveals that walls within walls and secluded apartments in the ciudadelas preserved stratification between the ruling elite and the middle and working classes

The NMAI telephone was a “a tool designed for an executive level of communication”-perhaps for a courtier-like assistant required to speak into a gourd mouthpiece from an anteroom, forbidden face-to-face contact with a superior conscious of status and of security concerns,” Matos says.

Would it not be ironic if the first telephone in the western hemisphere was invented by a n ancient civilization with now written language?

The Chimu telephone is an excellent example of showing our ancestors had ideas and inventions that in many ways are similar to our modern ones.

Just like, the Chinese scholar Zhang Heng created an instrument that could determine the direction of an earthquake the Chimu people felt a need to invent something that provides them with better means of communication.

The result was the NMAI telephone!

In other words, ancient people faced problems and solved them by creating objects that could be helpful in their daily lives. We do the same today.

© MessageToEagle.com