Tiny Notebook Reveals Leonardo Da Vinci’s First Statement Of The Laws Of Friction

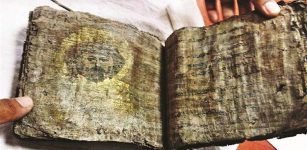

MessageToEagle.com – A tiny notebook reveals Leonardo Da Vinci’s first statement of the laws of friction. Scribbled notes and sketches on a page in the book have been identified as the place where Leonardo Da Vinci first recorded his understanding of the laws of friction. The old notes were previously dismissed as irrelevant by an art historian, but new research shows they are very significant indeed.

The research conducted by Professor Ian Hutchings, Professor of Manufacturing Engineering at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of St John’s College also shows that Da Vinci went on to apply this knowledge repeatedly to mechanical problems for more than 20 years.

It is widely known that Leonardo conducted the first systematic study of friction, which underpins the modern science of “tribology”, but exactly when and how he developed these ideas has been uncertain until now.

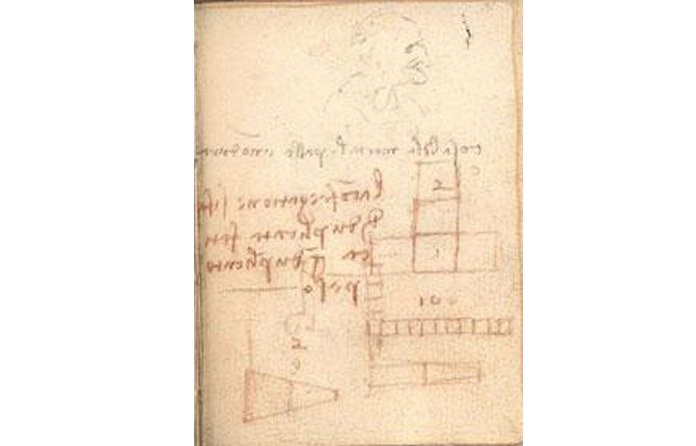

Ironically the page had already attracted interest because it also carries a sketch of an old woman in black pencil with a line below reading “cosa bella mortal passa e non dura”, which can be translated as “mortal beauty passes and does not last”. Amid debate surrounding the significance of the quote and speculation that the sketch could represent an aged Helen of Troy, the Director of the V & A in the 1920s referred to the jottings below as “irrelevant notes and diagrams in red chalk”.

Professor Hutchings’s study has, however, revealed that the script and diagrams in red are of great interest to the history of tribology, marking a pivotal moment in Leonardo’s work on the subject.

See also:

Did Leonardo Da Vinci Invent Contact Lenses In 1508?

Rare Leonardo Da Vinci Self-Portrait With “Magical Powers” Hidden From Hitler Is Now On Display

The Parachute Was Invented By Ancient Chinese – Not Leonardo Da Vinci

The rough geometrical figures underneath Leonardo’s red notes show rows of blocks being pulled by a weight hanging over a pulley – in exactly the same kind of experiment students might do today to demonstrate the laws of friction.

Professor Hutchings said: “The sketches and text show Leonardo understood the fundamentals of friction in 1493. He knew that the force of friction acting between two sliding surfaces is proportional to the load pressing the surfaces together and that friction is independent of the apparent area of contact between the two surfaces. These are the ‘laws of friction’ that we nowadays usually credit to a French scientist, Guillaume Amontons, working two hundred years later.”

According to Professor Hutchings, Leonardo’s sketches and notes were undoubtedly based on experiments, probably with lubricated contacts. He appreciated that friction depends on the nature of surfaces and the state of lubrication and his use and understanding of the ratios between frictional force and weight was much more nuanced than many have suggested. Although he undoubtedly discovered the laws of friction, Leonardo’s work had no influence on the development of the subject over the following centuries and it was certainly unknown to Amontons.

MessageToEagle.com