South America’s Icefields – Larger Than All Glaciers In The European Alps Together

Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com – Not much is known about the Patagonian icefields in the Andes of South America.

Despite their massive size, spanning around 16,000 square kilometers – roughly the same size as Thuringia state in Germany.

Credit: Dr. Johannes Fürst

A team led by Johannes Fürst from the Institute of Geography at FAU – using cutting-edge methods and the rather scarce data available to date – re-estimated the volume of both icefields to be 5,351 cubic kilometers in 2000.

The results of this re-estimations show that the combined ice volume of the two ice caps is a whopping forty times greater than the combined glaciers in the European Alps.

The Patagonian icefields have really huge dimensions. The Northern Patagonian Icefield alone is approximately 120 kilometers long and, in some places, between 50 and 70 kilometers wide.

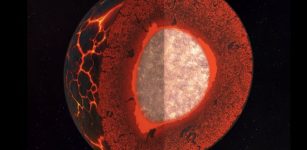

The South Patagonian Icefield is a colossal natural wonder, spanning over an impressive 350 kilometers from north to south and averaging between 30 to 40 kilometers in width. The ice masses there are incredibly dense, with an average thickness of over 250 meters. This makes them about five times thicker than the glaciers found in the European Alps – quite a remarkable comparison!

The climate here is quite unique and sometimes extreme. Just like in Central Europe, the winds in these South American regions typically move from west to east, bringing moist air from the oceans inland. What sets it apart are the Andes mountains that run north to south across South America. Their heights vary from less than 3,000 meters in the southern parts to a whopping 6,000 meters in subtropical and tropical areas. This forces the incoming damp air from the Pacific to ascend.

As the air cools down, it is only able to hold less moisture, and it begins to rain or snow, depending on the altitude and time of year.

The regions between the Pacific coast and the Andes often have more than 3,000 millimeters of precipitation per year. This means that 3,000 liters of rain, snow, or hail fall on each square meter of land per year, comparing with Nuremberg and Munich, for example, that have approximately 550 and 930 liters, respectively.

Both Patagonian icefields are, therefore, located in a remote region of the world where considerably fewer climate and geographic data are gathered than in Central Europe, for example.

In addition, Argentina and Chile have been in dispute over the exact position of the border for a long time now, and they have come to a deadlock over the exact position of the Southern Patagonian Icefield, basically declaring wide stretches of the glacier to be a no man’s land and making it extremely difficult to access. Not only that, it means that it is virtually impossible to take geographical measurements in situ.

Credit: Dr. Johannes Fürst

A natural phenomenon also hinders research in the area. Precipitation increases with each meter that the air rises on the western slopes of the Andes. It, therefore, snows in vast quantities on the summits and on both Patagonian icefields.

“We do not know exactly how much precipitation actually falls there, however,” explains FAU researcher Johannes Fürst, in a press release.

The large volumes of snow that fall at these high altitudes make it unfeasible to operate a weather station in such a remote location. Any weather station would be susceptible to damage from the massive quantities of snow that fall in the region, and repairs would prove extremely difficult and time-consuming.

No one can know for sure whether 10,000 or even up to 30,000 liters of precipitation fall there per square meter each year. “It is speculated that the maximum snowfall lies between 30 and 100 meters per year,” says Johannes Fürst. “Those are unimaginable quantities.”

As the ice of the glacier is formed over time from these masses of snow, accurate figures would allow researchers to gain a better understanding of the processes. One thing is for sure: The huge quantities of precipitation are a reliable and plentiful source of replenishment for the ice cap, with the ice it forms soon also joining the flow down towards the valley.

As a result, the glaciers coming from the Patagonian ice fields flow extremely rapidly. While the ice in the European Alps only rarely covers a distance of one hundred meters per year, most of the glaciers in the Patagonian icefields move more rapidly than this.

Research led by Matthias Braun from the Institute of Geography at FAU indicates that climate change is causing the glaciers in the Patagonian icefields to lose an average of one meter in thickness annually.

That is exactly what the FAU-lead team has now done in close collaboration with Chilean research organizations.

Now the researchers can gather data about the ground under the ice. Accordingly, they can estimate much more accurately how quickly a glacier can be expected to disappear in the future. For example, the ice may be hiding a hollow in the ground.

If the glacier retreats, its meltwater may turn this hollow into a lake. As long as these lakes are in contact with the ice, the relatively warm water can attack the glacier from below. This can lead to more ice breaking off from the ice front and accelerate the retreat of the glacier even further.

The FAU glaciologists, therefore, have good reasons for measuring the Patagonian ice cap in situ. They fly over the glacier with a helicopter and use radar beams to measure the depth of the ice to within a few meters. This leads to a considerable improvement in the data available on this extremely dynamic ice.

The research will still focus on the icefields in order to be able to keep track of dangerous developments more closely than has been possible until now.

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com Staff Writer