Jan Bartek – MessageToEagle.com – The study of our ancient ancestors’ migration paths to the territories they eventually inhabited remains a subject of considerable interest. Researchers have introduced an innovative model elucidating how the first anatomically modern humans settled in Europe.

This “Our Way Model,” crafted by an interdisciplinary team from the University of Cologne’s Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology alongside the Department of Prehistoric Archaeology, is predicated on analyzing movements and population densities across time and space during the Aurignacian period, approximately 43,000 to 32,000 years ago.

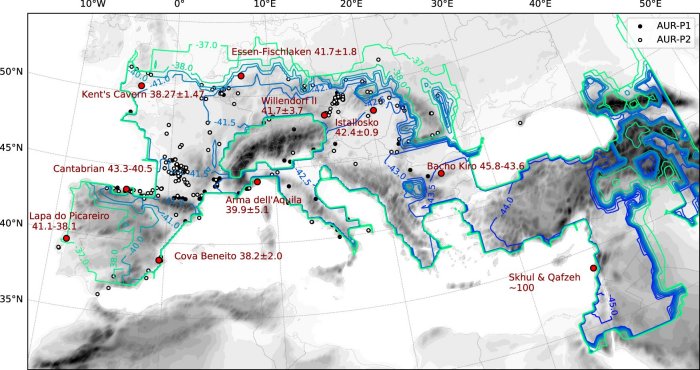

Contours of the arrival time of human expansion in ka, defined by population density reaching 0.4 P 100 km−2 for the first time. Credit: Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51349-y

Collaboration between climate scientists and archaeologists reveals how climate change influenced human dispersal. Early anatomically modern humans, who lived as hunter-gatherers for extensive periods, began spreading across Europe when global climatic conditions differed significantly from today. The late Last Glacial Period was characterized by a cooler and drier climate, punctuated by warmer interglacial periods that varied in their abruptness or gradual nature.

The reasons behind human dispersal to Europe were likely multifaceted, including the innate human drive to explore, shifts in social structures, and technological advancements. However, the newly developed model has enabled researchers to clearly illustrate the impact of climate change on these migration patterns.

Previous models of long-term human population dispersals often used diffusion-reaction equations, showing slow, continuous dispersal due to population growth. Agent-based models focus on individual or group migration motivations at smaller scales. Recent models incorporate paleoclimate data and use Net Primary Production as a proxy for food availability and human mobility. However, this approach overlooks the accessibility of food sources since only a fraction was usable by humans.

The research team believes early habitation in Europe involved complex processes like advance, retreat, abandonment, and resettlement driven by climate changes and human adaptability. The “Our Way Model” simulates human dispersal by combining climate and archaeological data to model Human Existence Potential (HEP), then modeling population dynamics within HEP limits. HEP estimates human existence likelihood under specific climate conditions for a culture using paleoclimatic data from known sites. A machine learning approach determines the climatic preferences of the Aurignacian culture. The model estimates spatial and temporal HEP patterns using Global Climate Model data and oxygen isotope data from Greenland ice cores.

Four Migration Phases

The Our Way Model reveals four distinct phases of the process.

The first phase indicates that an initial phase of relatively gradual westward expansion from the Levant to the Balkans, occurring approximately 45,000 to 43,000 years ago, was succeeded by a second phase characterized by swift expansion into Western Europe between approximately 43,250 and 41,000 years ago. Despite encountering brief setbacks during this period, Homo sapiens populations rapidly grew to an estimated size of 60,000 individuals across Europe, occupying all known archaeological sites from this era.

Credit: Adobe Stock – Alla

The subsequent third phase witnessed a decline in both the size and density of the human population and the area they occupied between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago. This decline was attributed to a prolonged severe cold lasting nearly 3,000 years, known as the GS9/HE4 period. Nevertheless, according to the model presented in this study, humans managed to survive within climate refuges provided by large topographical features such as the Alps—regions they had settled during the preceding phase.

During the fourth phase, approximately 38,000 years ago, improved HEP conditions led to a rapid recovery and expansion of the population. This growth was marked by increased population density in specific regions and further exploration into previously uninhabited Great Britain and the Iberian Peninsula areas. These developments align with archaeological findings. The HEP maps suggest that by the end of this period, some human populations had adapted more effectively to cold climates than others, enabling them to extend their reach into new environments.

“Regional studies can hardly capture all factors at play when trying to reconstruct human dispersal, including how they work together at different scales and contribute to overall long-term trends. This is a major advantage of the new modeling approach,” said Dr. Isabell Schmidt at the Department of Prehistoric Archaeology.

The study was published in Nature Communications

Written by Jan Bartek – MessageToEagle.com – AncientPages.com Staff Writer