Our Bodies Have Transformed And Become Weaker Over The Millennia – Male Farmers 7,300 Years Ago Had Strong Legs Of Marathon Men

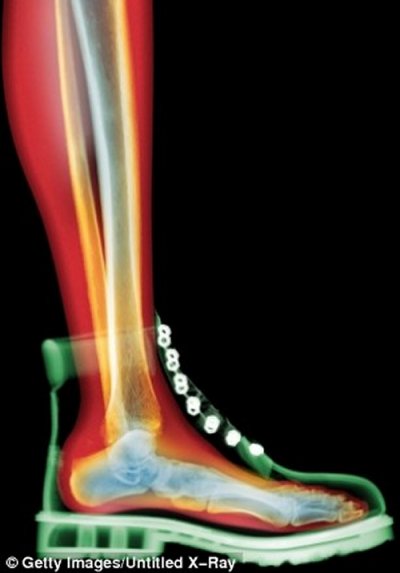

MessageToEagle.com – Researchers have discovered that human leg bones have grown weaker since farming techniques were invented but male farmers 7,300 years ago had strong legs of cross-country runners.

Humans have been transformed from athletes to couch potatoes following advances in farming over the last 6,000 years, according to a new study.

“My results suggest that, following the transition to agriculture in central Europe, males were more affected than females by cultural and technological changes that reduced the need for long-distance travel or heavy physical work,” lead researcher Alison Macintosh, Cambridge University

anthropologist, who has has tracked the weakening of the human race by studying bones from grave sites across central Europe.

She found that as new technology contributed to an easier life over the ensuing millennia, humans became further removed from their athletic ancestors.

“This also means that, as people began to specialize in tasks other than just farming and food production, such as metalworking, fewer people were regularly doing tasks that were very strenuous on their legs,” she said.

The earliest skeletons examined dated back to around 5,300 BC and the most recent to 850 AD, a time span of 6,150 years.

They show that after the emergence of agriculture, the leg bones of people living along the Danube river valley became progressively less strong.

A comparison was made with a previous assessment of the bone strength of Cambridge University undergraduates, which showed that the earliest male farmers, dating back around 7,300 years, had legs on a par with those of student cross-country runners today. But within just over 3,000 years, average mobility had dropped to the level of students rated as “sedentary”.

Ms Macintosh used a portable 3D laser surface scanner to study the femurs, or thigh bones, and tibiae, or shin bones, of skeletons from Germany, Hungary, Austria, the Czech Republic and Serbia.

She found that male tibiae became less rigid and the bones of both men and women became less strengthened to loads in one direction more than another.

“Both sexes exhibited a decline in anteroposterior, or front-to-back, strengthening of the femur and tibia through time, while the ability of male tibiae to resist bending, twisting, and compression declined as well,” Ms Macintosh, who presented her findings today at the annual meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in Canada, said.

Evidence of declining mobility in women was less consistent than for men but Iron Age women from between 1,450 and 850 BC bucked the general trend and appeared to have the strongest thigh bones of all the females examined.

One explanation could be that the Iron Age sample included skeletons from the Hungarian Scythians, known for their Amazonian female warriors who participated in combat.

However, if the strength seen in the thigh bones of Iron Age women was due to high mobility, it should be seen in their shin bones as well – but it was not.

“It could be something other than mobility that is driving this Iron Age female bone strength, possibly a difference in body size or genetic,” Ms Macintosh said.

“In central Europe, adaptations in human leg bones spanning this time-frame show that it was initially men who were performing the majority of high-mobility tasks, probably associated with tending crops and livestock.”

“But with task specialization, as more and more people began doing a wider variety of crafts and behaviors, fewer people needed to be highly mobile, and with technological innovation, physically strenuous tasks were likely made easier.

“The overall result is a reduction in mobility of the population as a whole, accompanied by a reduction in the strength of the lower limb bones.”

The study has been presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in Calgary, Canada.

MessageToEagle.com