Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com – These strange “moss balls” have long been a mystery. They are usually found in lakes in the northern hemisphere, particularly Japan and Iceland.

In Japan these little green balls are protected species and they are of great cultural. They are also very popular with aquarium owners, although, in recent years, their popularity has resulted in a significant decline.

Credit: Dora Cano-Ramirez and Ashutosh Sharma

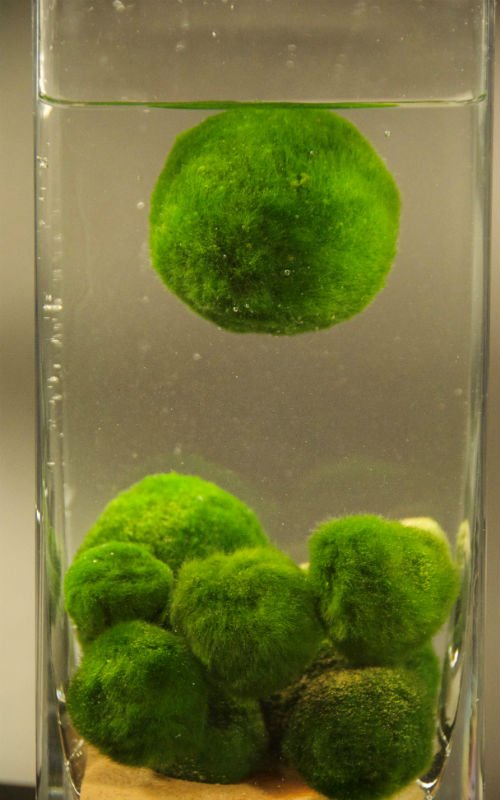

At first sight they may look like cute ‘”moss balls”, but they are really a rare form of marimo algae and scientists have tried to figure out why they sink at night and float during the day.

Now a group of scientists from the University of Bristol say they have solved the mystery of the strange “moss balls”.

Biological Clock Decides When To Float And Not

In a press release, researchers explained that the photosynthesis and daily circadian rhythms are responsible for the floating and sinking of the balls.

When these aquatic plants photosynthesise, they become covered in tiny bubbles of oxygen, which the scientists predicted was the cause of their buoyancy.

They tested their theory by using a chemical that stops photosynthesis. The chemical stopped bubbles forming, so the marimo did not float.

An aggregation of marimo balls in the laboratory, with one that has become buoyant. Credit: Dora Cano-Ramirez and Ashutosh Sharma

The lab then investigated whether the photosynthesising surface of the algae balls had a biological “clock” or circadian rhythm.

Marimo were kept under dim red light for several days. They discovered that if the marimo were then given bright light at the time that corresponded to the start of the day, they floated much more rapidly than if they were given light at the middle of the day.

This shows that marimo floating is controlled by their biological clock.

See also:

The study may have future implications for conserving marimo, which have experienced a global decline.

“Unfortunately, marimo balls are endangered, being currently found in only half the lakes where they were once spotted.

“This might be caused by changes in light penetration due to pollution. By understanding the responses to environmental cues and how the circadian clock controls floating, we hope to contribute to its conservation and reintroduction in other countries,” PhD student Dora Cano-Ramirez, lead author of the study said.

The team’s research has been published in the journal Current Biology.

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com Staff Writer