MessageToEagle.com – Experts are still divided over Por-Bajin, a mysterious 1,300-year-old fortress-like structure located on island in middle of lake.

With its island location and towering square walls that were once impenetrable, it looks at first glance to be an ancient fortress especially constructed to keep out enemies.

There are also those who believe the 1,300-year-old structure in rural Siberia has more mystical properties and might have been a summer palace, monastery, or even an astronomical observatory. Whatever it is, more than a century after it was first explored, archaeologists have no unlocked the secrets of Por-Bajin. It still remains unknown who built it or why.

Most likely constructed in 757 AD, the complex has fascinated and frustrated experts in equal measure since it was located in the middle Tere-Khol, a high-altitude lake in Tuva, in the late 19th century.

First explored in 1891, with small-scale excavation work later carried out between 1957 and 1963, it was not until 2007 that proper research took place at the site.

Archaeologists found clay tablets of human feet, faded colored drawings on the plaster of the walls, giant gates and fragments of burnt wood. But nothing yet has provided a definitive answer as to why the structure was built, and excavation work continues.

‘Por-Bajin is legally treated as one of the most mysterious archaeological monuments of Russia,’ says the official website for the complex, about 3,800km from Moscow.

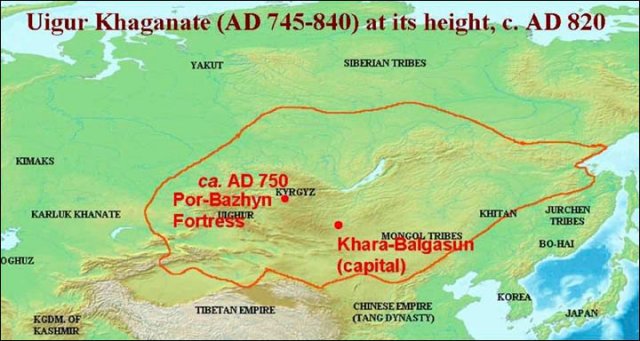

‘Apparently it was built at the period of the Uighur Khagante nomadic empire (744-840 AD), but it’s not clear what they built a fortress for in such a solitary place, far from big settlements and trade routes. ‘The architecture also produces many questions and it has reminders of a model of an ideal Chinese city-palace.’

Por-Bajin, which translates as ‘clay house’ in the Tuvan language, is located in the very centre of Eurasia, on the borders of Russia and Mongolia. It sits on a small island in a lake high in the mountains between the Sayan and Altai ranges, about five miles west of the isolated Kungurtuk settlement in southern Siberia. Laser mapping of the site prior to the first major excavation in 2007 helped experts build a 3D model of what the community might have looked like. Despite its age, parts of the structure were well preserved when archaeologists arrived to examine the 3.5 hectare site, with walls clearly visible.

Outer walls standing 10 metres tall and 12 metres wide formed a rectangular shape, creating what many have interpreted as a protective kremlin-like fortress.

A main gate was discovered, opening into two successive courtyards connected by another gate.

Walls on the inside were smaller, at about one metre-tall, forming the outline of buildings, with a large building in the centre of the site. Some of the walls and panels were covered with lime plaster painted with horizontal red striped. The main complex in the inner courtyard had a two-part central structure, one behind the other linked by a covered walkway. It had a tiled roof and was supported by 36 wooden columns resting on stone bases.

Construction materials, and the way the site is laid out, told the experts it was built in a typically Chinese architectural tradition, most likely in the second half of the eight century.

‘The building was most likely of the post-and-beam construction characteristic of Chinese architecture from the T’ang Dynasty,’ wrote head archaeologist Irina Arzhantseva in a report published in The European Archaeologist in 2011.

‘Finds of burnt timber fragments point to the use of the typical Chinese technique of interlocking wooden brackets, called dou-gung. Ramps led down to the two flanking galleries which were roofed, open spaces looking onto the access to the main pavilion.’

While debate continues about the use of Por-Bajin, there is growing evidence it was a community or palace complex centred around a Buddhist monastery. Certainly, there is an argument that its layout is typical of the palaces of the Buddhist Paradises as depicted in T’ang paintings.

Books from the era also describe the existence of Uighur towns, extensive building activities, and a transition from a nomadic to sedentary lifestyle. Indeed, there may have been as many of 15 of these settlements in Tuva alone, all square of rectangular shaped and enclosed by walls with a main gate.

What puzzles the experts, however, is the lack of rudimentary heating systems, particularly given that Por-Bajin sits at 2,300metres above sea level and endures harsh Siberian weather.

If anything it suggests that the complex was only ever occupied for a brief period of time, or was used as a seasonal home in the warmer summer months. Some experts even say that the climate, or other natural occurrences in the region, brought occupation of the site to an early end in the 9th century.

Por-Bajin sits on a bed of permafrost with evidence that the melting of this ice – as a result of warmer temperatures over the past century – has caused not only a destruction of the walls, but a dramatic rise in the depth of the lake water.

‘This situation created a two-fold threat to the long-term survival of the site. Thermokarst (melting of the permafrost) seems to undermine the stability of the structures on the site, leading to collapse and decay; and frost fissures are causing constant erosion of the banks of the island to such an extent that it is estimated that the walls will start collapsing into the lake in about 80 years.

‘Archaeological and geomorphological fieldwork revealed traces of at least two earthquakes which had accelerated the natural process of deterioration. The first of these seems to have happened already during the construction of the ‘fortress’ in the 8th century.

‘It is not yet quite clear how long the buildings survived after the abandonment of the site in the 9th century, but some time after the abandonment there was another catastrophic earthquake which led to fires and to the collapse of the southern and eastern enclosure walls, and destroyed the north-western corner bastion,’ Irina Arzhantseva wrote in the 2011 research paper.

While debate on its origins will no doubt continue for decades, those who have seen Por-Bajin are all in agreement about its beauty. In fact, in many ways Russian president Vladimir Putin sums it up perfectly.

‘I have been to many places, I have seen many things, but I have never seen anything of the kind,’ he said, following a visit to the complex with Prince Albert of Monaco in 2007. Few could argue with that.

MessageToEagle.com