MessageToEagle.com – About 3,000 years ago, the biblical Solomon, a king of Israel and son of King David, was renowned for his fabled wisdom, power and his personal fortune.

Ancient sources tell King Solomon’s wealth was one of the largest in the world.

Galleys arrived off the scorching shores of Palestine, loaded with fabulous treasures for this legendary king.

As the banks of rowers glided their vessels into the harbor, slaves rushed to the dockside to unload the precious cargo – silver, sweet-smelling sandalwood, wine, ivory, apes and peacocks.

Most precious was gold and King Solomon according to the Old Testament, King Solomon was the possessor of tons of gold.

His drinking cups were made of gold and he had 300 golden shields. His great throne in Jerusalem was ivory ‘overlaid with the best gold’, and on steps leading up to it stood 12 golden lions facing 12 golden eagles.

A seven-branched candelabra of gold hung above his royal seat. The walls of the Temple he built to house the Ark of the Covenant were adorned with it, too.

But where did this wealth come from? In the Bible it is written that Solomon’s servants, traveled to Ophir ‘and fetched from thence gold, 420 talents’ – roughly 20 tons. But that is where the clues stop and the trail goes cold. The location of Ophir, it seems, was meant to remain a mystery. The true location of legendary Ophir has never been established.

This has not stopped historians and archaeologists from looking for the place that was famous for its magnificent gold.

Out of this mystery grew a tale that obsessed the ancient Greeks, Renaissance adventurers and Victorian explorers and, with its aura of romance and greed, still has the power to draw us in today. Indeed, the search for King Solomon’s mines is as timeless as that for the Holy Grail.

The astronomer and geographer Ptolemy calculated that Ophir was located in what today is Pakistan, at the mouth of the Indus river.

Alternatively, he placed it near the Straits of Malacca, between Malaysia and Indonesia.

A Portuguese explorer of the 15th century, meanwhile, claimed it was in the Shona lands of Zimbabwe in Africa, a link embraced by the English poet John Milton in his epic poem Paradise Lost.

Either way, the prospect of boundless booty inspired ambitious men to set sail into vast and dangerous oceans and stretch the limits of the known world.

Christopher Columbus believed he had found Ophir in Haiti, and Sir Walter Raleigh in the jungles of Surinam.

In 1568 a Spanish captain discovered an archipelago in the Pacific and named them the Solomon Islands because he believed they were Ophir.

Just over a century ago, the Victorians were captivated by a tale of British grit, ancient curses, African warriors and black magic, all suffused with the glamour of diamonds and gold.

While Solomon’s famed wealth is a story as old as the ages, the popular fascination with locating a portion of this fantastic fortune is a far more recent affair. The idea of mines full of riches was first introduced in the late 19th century by author H. Rider Haggard in his blockbuster adventure novel, King Solomon’s Mines, whose publication coincided with a boom in archeological discoveries of ancient sites in the Middle East and Africa.

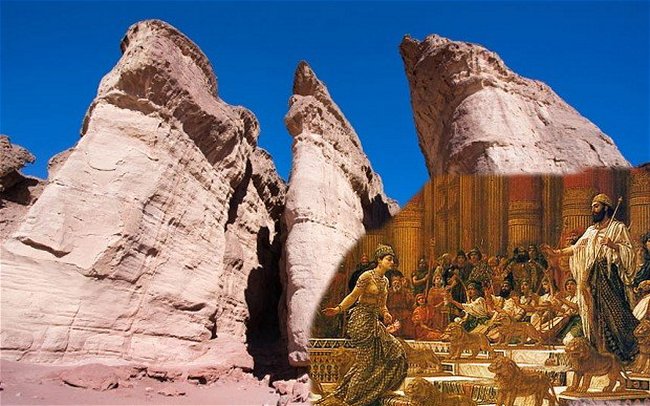

Half a century later, Nelson Glueck, American rabbi and archaeologist made headlines of his own when he announced that he had located Solomon’s mines in the Great Rift Valley near the modern-day boundary of Israel and Jordan. These mines, however, weren’t filled with gold-they were extensive copper-smelting plants that Glueck maintained were the true source of Solomon’s wealth. Unable to connect archaeological evidence to biblical accounts, however, modern historians soon began to doubt Glueck’s connection of Solomon to the region’s copper production.

For the past few decades, conventional wisdom has held that the ancient Egyptians built most of the mines in the region during the 13th century B.C.-a theory supported by the discovery of an Egyptian temple at the complex in 1969.

In 2008, however, researchers located a mining site in neighboring Jordan (known as Khirbat en-Nahas) that archaeological evidence suggested became operational 300 years later that previously assumed, during the 10th century B.C. The following year, another excavation identified a site in Israel’s Timna Valley, dubbed Site 30, which was home to a cooper-smelting camp also believed to have been built in same time period as the Jordanian mine- likely too late for an Egyptian settlement but squarely within the biblical timeframe for Solomon’s famed mines.

See also:

In 2013, Dr. Erez Ben-Yousef, an archaeologist from Tel Aviv University led a dig in a previously unexamined section of the site known as Slaves’ Hill. His team uncovered archaeological evidence of dozens of the furnaces used to smelt copper as well as layers of cooper slag, a by-product of the smelting process.

The team also found a trove of personal items, including clothing, ceramics, fabrics and tools, and the remnants of a variety of food items, indicating a highly developed, long-term settlement at the site. Nearly a dozen artifacts from the Slaves’ Hill site, including date and olive pits, were sent to the University of Oxford for radiocarbon dating, which confirmed their age to the 10th century B.C., reinforcing their belief that the sites were not Egyptian.

It’s hoped that these most recent revelations will help convince the archaeological community of the unlikelihood that the Egyptians constructed and controlled the important copper-smelting centers in the region, but the researchers stress that though the sites date to the time of the fabled King Solomon, there is no evidence that he or his Israelite tribe were the ones who built the mines. In fact, there is strong evidence to suggest that it was another group mentioned in the Bible, the Edomites, who actually controlled the operations.

The Edomites were a semi-nomadic tribe, usually depicted in the Bible as a traditional enemy of the Israelites before their eventual forced conversion to Judaism in the 2nd century B.C. Their early civilization thrived on trade, but by the time of the construction of the copper-smelting mines at Khirbat en-Nahas and the Timna Valley more than 3,000 years ago, they had developed into a highly organized state. Tens of thousands of workers toiled away at these desert sites-some of the largest copper-smelting mines in the ancient world

However, despite all attempts no-one has been able to locate the mines of King Solomon and the mysterious land of Ophir. The mines and Ophir remain as elusive as ever.

MessageToEagle.com

References:

The Search Continues for King Solomon’s Mines