Meteor Showers On Mercury May Explain Astronomical Puzzle

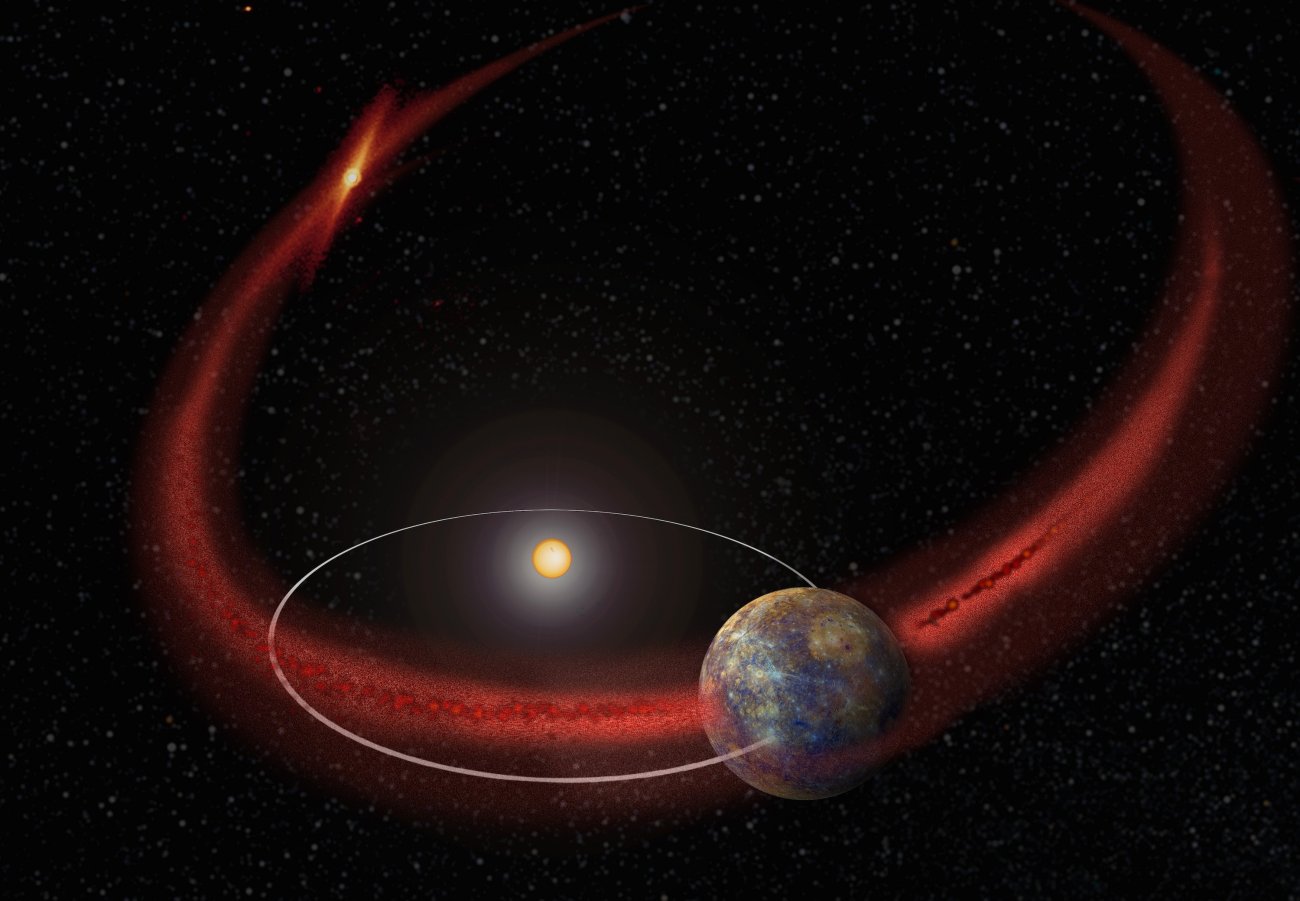

MessageToEagle.com – Mercury can experience meteor showers as Comet Encke periodically peppers the planet’s tenuous atmosphere with dust, new research suggests.

Earth has several meteor showers every year, generally occurring when the planet plows through the dust trail left behind by a comet or asteroid passing near the sun. These particles fall into the atmosphere and burn up, creating a trail for skywatchers to follow.

Research also suggests that Mars likely got a flurry of meteors a year ago, when Comet Siding Spring made a close pass by the Red Planet. Compared to Earth’s and Mars’ atmospheres, Mercury’s is much less substantial — made of just clouds of atomic particles formed from surface ejections or the solar wind — but the particles still have an effect on the exosphere, the outer fringe of its atmosphere. [The Most Enduring Mysteries of Mercury]

The new Mercury finding came after scientists were puzzled by a strange pattern in calcium observed in the thin atmosphere of the crater-filled planet.

Based on observations from NASA’s MESSENGER (Mercury Surface Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging) spacecraft, scientists found that calcium measured near the planet’s surface varies regularly through Mercury’s year. Usually, the calcium peaks just after Mercury is at its closest point to the sun, called perihelion. (MESSENGER concluded its mission earlier this year.)

A mystery arose, however, when a model predicted that Mercury’s calcium peak should instead occur just before perihelion, based on when the planet moves through interplanetary dust near the sun.

The researchers thought that Comet Encke might be responsible. With the comet’s short orbit of just 3.3 years, the sun’s energy has affected the body so much that a dense dust stream formed over millennia. But the timing was still a puzzle: At first, the team thought the comet’s dust could hit Mercury’s surface and blast calcium particles from the planet into space, but the calcium peak falls a week before Encke’s closest approach to Mercury.

To learn more, the researchers modeled Encke’s orbit over the course of tens of thousands of years. The model suggested that the comet’s dust trail spreads along the path of the comet. When the effects of sunlight are taken into account, the light’s slight drag on Encke’s ejected dust grains greatly changes their orbits over a period of years.

In the model, the dust stream eventually lagged behind Encke, to a spot similar to where the calcium peak was observed in real life. Dust grains that were bigger and younger, ejected a relatively short time ago, were not shifted as much as older, smaller grains were.

In other words, the model seems to predict that grains about a millimeter in size, ejected from Encke between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago, would hit Mercury right when the calcium peak occurs.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences, held in Maryland in October. Researchers participating in the study included Apostolos Christou, of the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland; Rosemary Killen, of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland; and Matthew Burger, of Morgan State University in Baltimore, who also works at Goddard.

A paper on the research also appeared in the Sept. 28 issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

MessageToEagle.com via Space.com

This article was originally published on Space.com – the leading space news site on the web keeping up on the latest space science, technology and astronomy news.