Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com – A hibernation-like state in an animal that lived in Antarctica during the Early Triassic, some 250 million years ago, has been analyzed by researchers at the University of Washington.

A survival strategy known as hibernation has been used by animals – especially those that live close to or within polar regions. This state helps them to get through the harsh winter months when food is limited, temperatures drop and days are dark.

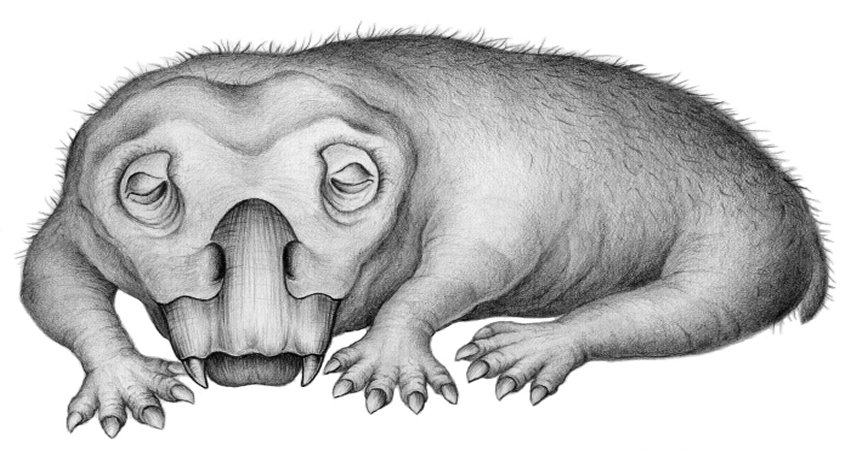

Life restoration of Lystrosaurus in a state of torpor. Credit: Crystal Shin

During Lystrosaurus’ time the region of Antarctic Circle, like today, experienced long periods without sunlight each winter.

The researchers analyzed a specimen of Lystrosaurus discovered in Antarctica and found that the creature, a member of the genus Lystrosaurus, was a distant relative of mammals. It lived during a dynamic period of our planet’s history, arising just before Earth’s largest mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period—which wiped out about 70% of vertebrate species on land—and somehow surviving it. The stout, four-legged foragers lived another 5 million years into the subsequent Triassic Period and spread across Earth’s then-single continent, Pangea, which included what is now Antarctica.

“The fact that Lystrosaurus survived the end-Permian mass extinction and had such a wide range in the early Triassic has made them a very well-studied group of animals for understanding survival and adaptation,” said co-author Christian Sidor, a UW professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum.

Today, Lystrosaurus fossils are found in India, China, Russia, parts of Africa and Antarctica.

These creatures most were roughly pig-sized, but some grew 6 to 8 feet long—had no teeth but bore a pair of tusks in the upper jaw, which they likely employed to forage among ground vegetation and dig for roots and tubers.

“Animals that live at or near the poles have always had to cope with the more extreme environments present there,” said lead author Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University.

“These preliminary findings indicate that entering into a hibernation-like state is not a relatively new type of adaptation. It is an ancient one.”

Lystrosaurus lived during a dynamic period of our planet’s history, arising just before Earth’s largest mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period—which wiped out about 70% of vertebrate species on land—and somehow surviving it.

Lystrosaurus tusks grew continuously throughout their lives. The cross-sections of fossilized tusks can harbor life-history information about metabolism, growth and stress or strain. Whitney and Sidor compared cross-sections of tusks from six Antarctic Lystrosaurus to cross-sections of four Lystrosaurus from South Africa.

The tusks from the two regions showed similar growth patterns, with layers of dentine deposited in concentric circles like tree rings. But the Antarctic fossils harbored an additional feature that was rare or absent in tusks farther north: closely-spaced, thick rings, which likely indicate periods of less deposition due to prolonged stress, according to the researchers.

“The closest analog we can find to the ‘stress marks’ that we observed in Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks are stress marks in teeth associated with hibernation in certain modern animals,” Whitney said.

The researchers cannot definitively conclude that Lystrosaurus underwent true hibernation.The stress could have been caused by another hibernation-like form of torpor, such as a more short-term reduction in metabolism, according to Sidor.

“To see the specific signs of stress and strain brought on by hibernation, you need to look at something that can fossilize and was growing continuously during the animal’s life,” said Sidor. “Many animals don’t have that, but luckily Lystrosaurus did.”

If the analysis of additional Antarctic and South African Lystrosaurus fossils confirms this discovery, it may also settle another debate about these ancient, hearty animals.

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com Staff