Insect-Sized Jumping Robot That Can Traverse Challenging Terrains

Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com – MIT engineers developed an insect-sized jumping robot that can traverse challenging terrains and carry heavy payloads.

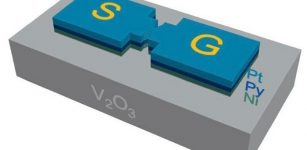

MIT researchers developed a hopping robot that can leap over tall obstacles and jump across slanted or uneven surfaces, while using far less energy than an aerial robot. Credit: Melanie Gonick, MIT

Insect-scale robots can squeeze into places their larger counterparts can’t, like deep into a collapsed building to search for survivors after an earthquake.

However, as they move through the rubble, tiny crawling robots might encounter tall obstacles they can’t climb over or slanted surfaces they will slide down. While aerial robots could avoid these hazards, the amount of energy required for flight would severely limit how far the robot can travel into the wreckage before it needs to return to base and recharge.

To get the best of both locomotion methods, MIT researchers developed a hopping robot that can leap over tall obstacles and jump across slanted or uneven surfaces, while using far less energy than an aerial robot.

The hopping robot, which is smaller than a human thumb and weighs less than a paperclip, has a springy leg that propels it off the ground, and four flapping-wing modules that give it lift and control its orientation.

The robot can jump 20 centimeters, four times its height, at a speed of 30 centimeters per second. It easily hops across ice, wet surfaces, uneven soil, and even onto a hovering drone while using 60% less energy than its flying counterpart.

Due to its light weight and durability, and the energy efficiency of the hopping process, the robot could carry about 10 times more payload than a similar-sized aerial robot, opening the door to many new applications.

“Being able to put batteries, circuits, and sensors on board has become much more feasible with a hopping robot than a flying one. Our hope is that one day this robot could go out of the lab and be useful in real-world scenarios,” says Yi-Hsuan (Nemo) Hsiao, an MIT graduate student and co-lead author of a paper on the hopping robot.

Maximizing efficiency

Jumping is common among insects like fleas and grasshoppers. Insect-scale robots typically fly or crawl, but hopping is more energy-efficient. A hopping robot converts potential energy into kinetic energy as it falls, back to potential on impact, and again to kinetic as it rises.

To maximize efficiency of this process, the MIT robot is fitted with an elastic leg made from a compression spring, which is akin to the spring on a click-top pen. This spring converts the robot’s downward velocity to upward velocity when it strikes the ground.

“If you have an ideal spring, your robot can just hop along without losing any energy. But since our spring is not quite ideal, we use the flapping modules to compensate for the small amount of energy it loses when it makes contact with the ground,” Hsiao explains.

As the robot bounces, its flapping wings provide lift and maintain the correct orientation for the next jump. Its four wing mechanisms use durable soft actuators that withstand repeated ground impacts without damage.

“We have been using the same robot for this entire series of experiments, and we never needed to stop and fix it,” Hsiao adds.

Key to the robot’s performance is a fast control mechanism that determines how the robot should be oriented for its next jump. Sensing is performed using an external motion-tracking system, and an observer algorithm computes the necessary control information using sensor measurements.

As the robot hops, it follows a ballistic trajectory. At the peak, it estimates its landing position and calculates the desired takeoff velocity for the next jump. While airborne, it flaps its wings to adjust orientation for proper angle, direction, and speed upon landing.

Durability and flexibility

The researchers put the hopping robot, and its control mechanism, to the test on a variety of surfaces, including grass, ice, wet glass, and uneven soil — it successfully traversed all surfaces. The robot could even hop on a surface that was dynamically tilting.

“The robot doesn’t really care about the angle of the surface it is landing on. As long as it doesn’t slip when it strikes the ground, it will be fine,” Hsiao says.

Since the controller can handle multiple terrains, the robot can easily transition from one surface to another without missing a beat.

For instance, hopping across grass requires more thrust than hopping across glass, since blades of grass cause a damping effect that reduces its jump height. The controller can pump more energy to the robot’s wings during its aerial phase to compensate.

Due to its small size and light weight, the robot has an even smaller moment of inertia, which makes it more agile than a larger robot and better able to withstand collisions.

The researchers showcased its agility by demonstrating acrobatic flips. The featherweight robot could also hop onto an airborne drone without damaging either device, which could be useful in collaborative tasks.

While the team showed a hopping robot carrying twice its weight, the maximum payload could be higher. Increased weight doesn’t reduce efficiency; instead, the spring’s efficiency is the main factor limiting how much it can carry.

Moving forward, the researchers plan to leverage its ability to carry heavy loads by installing batteries, sensors, and other circuits onto the robot, in the hopes of enabling it to hop autonomously outside the lab.

“Multimodal robots (those combining multiple movement strategies) are generally challenging and particularly impressive at such a tiny scale. The versatility of this tiny multimodal robot — flipping, jumping on rough or moving terrain, and even another robot — makes it even more impressive,” says Justin Yim, assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne, who was not involved with this work. “Continuous hopping shown in this research enables agile and efficient locomotion in environments with many large obstacles.”

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com Staff Writer