A. Sutherland – MessageToEagle.com – A near-death experience is one of the most enigmatic events in a human life. Yet in modern Western culture near-death accounts contain surprisingly similar elements.

In the past century, novelists, screenwriters and philosophers have consistently described a peaceful feeling and a journey toward a bright light, which is often followed by a meeting with deceased family members who tell the individual to return to earthly life.

Scientific records of the same era have an uncanny resemblance to the literary movement. Through personal experiences, patient accounts and experiments, medical researchers have been able to corroborate fictional depictions.

By analyzing the seemingly parallel narratives of both realms, Stanford scholar Laura Wittman has discovered the biological and cultural origins surrounding contemporary cultural assumptions about near-death experiences and the process of dying.

In the course of her research, Wittman, an associate professor of Italian and French, has investigated the portrayals of near-death scenarios from literature of the 1880s to contemporary films such as Flatliners (1990) and Brainstorm (1983), and in works of science fiction such as Bernard Werber’s Les Thanatonautes [The Deathonauts] (1994) and Connie Willis’ Passage (2001.)

“The codification of such an ephemeral experience,” Wittman said, set her “on the path of looking at literary accounts of near-death in the context of evolving scientific research, as well as sociological research on this topic.”

Wittman studied more than 60 “near-death medical thrillers” and other popular fictional accounts.

When it comes to near-death tales, neither science nor pop-culture operates in a cultural vacuum. Distinct as they are, Wittman said, the two areas “mutually influence each other.”

“For example,” she said, the currently common image of “seeing your whole life” like a “speeded-up film” was not present in literary or medical accounts from the turn of the 19th century. In older accounts, prior to the advent of cinema, people “tended rather to see one or two key moments from their lives or the entire life simultaneously, and that was how they sought some perspective on their own identity in their last moments.”

Wittman points to one of the earliest modern accounts describing a near-death experience – Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater [1821] – as an example of an early near-death experience narrative: “Having in her childhood fallen into a river … she saw in a moment her whole life … arrayed before her as in a mirror, not successively, but simultaneously … there was no pain or conflict … in a single instant succeeded a dazzling rush of light …”

See also:

Afterlife Is Real – Neurosurgeon Says He Has Proof Of Heaven And Advanced Higher Life-Forms

Death Is Just An Illusion: We Continue To Live In A Parallel Universe

Terminal Lucidity Phenomenon: Why Are Some People So Vigorous Shortly Before Dying?

Over the decades, near-death narratives found in fiction and film, Wittman said, “help to combat the growing invisibility of death in our culture, where it has become an essentially private, often terrifyingly lonely affair.”

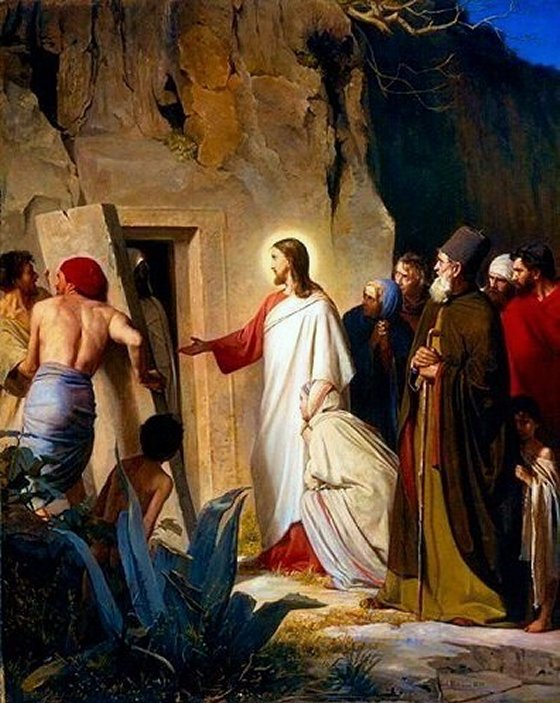

Wittman, chair of undergraduate studies in Italian and graduate studies in French and Italian, first became interested in the near-death experience after coming across various 19th- and 20th-century works by authors interested in the Biblical story of Lazarus.

In the Biblical account, Lazarus is a man Jesus raised from the dead who comes back to life without saying a word. Wittman found that his silence both fascinated and perplexed European fiction writers.

Numerous literary works, including novels and plays by acclaimed authors like D. H. Lawrence, Luigi Pirandello, Graham Greene, André Malraux and Eugene O’Neill, re-examined the Lazarus tale, and the figure of Lazarus became an emblem of near- death studies in the 20th century as a result. The story, Wittman said, “expresses uniquely modern anxieties about death and dying. Foremost is the desire to re-enchant death, turning it into a transformative journey rather than an ominous, unspecified ending.”

As Wittman dug deeper she noticed that the literary interest in Lazarus’ story coincided with a growth in scientific interest when, in the late 1880s, doctors started to collect testimony of visions and near-death travels from their patients. About a century later “neuroscientists,” as Wittman noted, “began to be interested in the phenomenon [of near-death experience] as a window into how the brain works.”

Wittman points to brain scientist and stroke survivor Jill Bolte Taylor’s memoir, My Stroke of Insight, as a contemporary example of a neuroscientist’s personal near-death experience narrative: “[M]y perception of my physical boundaries was no longer limited to where my skin met air. I felt like a genie liberated from its bottle.… My entire self-concept shifted as I no longer perceived myself as a single, a solid, an entity with boundaries that separated me from the entities around me. I understood that at the most elementary level, I am a fluid.”

As the field of medicine progressed, medical reports and memoirs of near-death experiences were joined by testimonies from people who had been brought back from the brink of death by improvements in medical technologies. By the middle of the 20th century, a cohesive narrative of the near-death experience had emerged both in popular literature and in medical narratives: the now-familiar vision involving some combination of seeing tunnels and lights, having a “life review” and experiencing the sensation of being pulled back into one’s body.

“This convergence,” Wittman said, “really showed me again that the supposed barriers between the humanities and the sciences are made much more by fear than by lack of interest in the same areas.”

In addition to writing a cultural history of near-death experiences, Wittman would like to build bridges between medicine and the humanities through an undergraduate class on near-death experiences presented through three academic perspectives: the humanities, medical ethics and cognitive neuroscience.

Wittman hopes that her research and potential course will open the door to more collaboration between the humanities and medicine, specifically with regard to the care of the terminally ill – resulting in what she says is a natural partnership between the two fields.

“I think here scientists and humanists are, in fact, interested in the same issues: why we see the world the way we do, how nature and nurture function together, what this means for our relation to others and the planet, what is life and if there is a ‘soul,'” she said.

Written by – A. Sutherland MessageToEagle.com Senior Staff Writer

Copyright © MessageToEagle.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of MessageToEagle.com