Earth’s Mantle Reveals Two Huge Subterranean ‘Islands’ – With The Size Of A Continent

Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com – Deep within Earth’s mantle lie two continent-sized ‘islands.’ Utrecht University new study reveals these regions are hotter and at least half a billion years old, possibly older, than the surrounding cold sunken tectonic plates.

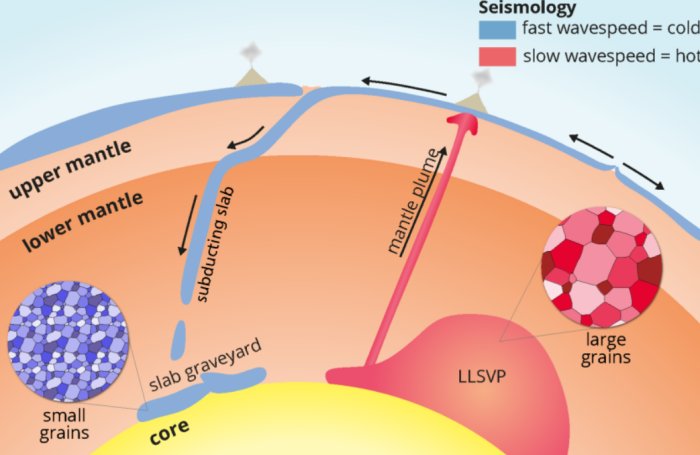

Location of the LLSVPs and a schematic representation of the Earth’s cross-section for speed and damping of the seismic waves. Credit: Utrecht University

These observations contradict the now-questioned theory of a well-mixed, fast-flowing Earth’s mantle. Large earthquakes make the Earth ring like a bell with various tones, akin to a musical instrument. Seismologists study Earth’s interior by examining how these tones are ‘out of tune,’ as whole Earth oscillations change when encountering anomalies.

This allows seismologists to image Earth’s interior, similar to how doctors use X-rays. Analysis of these oscillations revealed two subsurface ‘super-continents’: one under Africa and another under the Pacific Ocean, both over two thousand kilometers deep.

“Nobody knew what they are, if they are temporary or have been there for millions or billions of years,” says Arwen Deuss, a seismologist and professor. “These two large islands are surrounded by a graveyard of tectonic plates transported by ‘subduction,’ where one plate dives below another and sinks nearly three thousand kilometers deep.”

“We have known for years that these islands are located at the boundary between the Earth’s core and mantle. And we see that seismic waves slow down there.” Earth scientists therefore call these regions ‘Large Low Seismic Velocity Provinces’ or LLSVPs. “The waves slow down because the LLSVPs are hot, just like you can’t run as fast in hot weather as you can when it’s colder.”

Deuss and her colleague Sujania Talavera-Soza wanted to learn more about these regions. “We added information on the ‘damping’ of seismic waves, which is the energy lost as waves travel through Earth. We examined both how out of tune the tones were and their sound volume.”

Schematic representation of the process of subduction of tectonic plates and of a mantle plume rising from an LLSVP. In the latter, the mineral grains are larger than those in the subducted plates. Credit: Utrecht University

Talavera-Soza notes: “Contrary to our expectations, there was little damping in the LLSVP, making tones sound loud. However, we found significant damping in the cold slab graveyard, where tones were soft. In the upper mantle, it matched our expectations: it’s hot, and waves are damped—similar to feeling more tired when running in hot weather compared to cold.”

According to Deuss, grain size is crucial. Subducting tectonic plates have small grains due to recrystallization, increasing damping as waves lose energy at each boundary. LLSVPs show little damping, indicating they consist of larger grains.

Those mineral grains do not grow overnight, which can only mean one thing: LLSVPs are lots and lots older than the surrounding slab graveyards. Even more so: the LLSVPs, with their much larger building blocks, are very rigid. Therefore, they do not take part in mantle convection (the flow in the Earth’s mantle).

Thus, contrary to what the geography books teach us, the mantle cannot be well-mixed either. Talavera-Soza clarifies: “After all, the LLSVPs must be able to survive mantle convection one way or another.”

Earth’s mantle is key to studying the planet’s evolution and phenomena like volcanism and mountain building. Mantle plumes, hot material rising from deep within, cause surface volcanism in places like Hawaii, likely originating at LLSVP edges.

In this type of research, seismologists make good use of oscillations caused by really large earthquakes, preferably quakes that take place at great depths, such as the great Bolivia earthquake of 1994.

“It never made it into the newspapers, because it took place at a large depth of 650 km and luckily did not result in any damage or casualties at the Earth’s surface,” Deuss explains.

Whole Earth oscillations are described mathematically to separate damping (loudness) from wave speed (tuning). Impressively, damping makes up only one-tenth of the information we can extract from these oscillations.

For this type of research, it is not necessary to wait until another earthquake occurs. The data from previous earthquakes is just as useful.

“We can go back to 1975, because from that year onwards, seismometers became good enough to give us data of such high quality that they are useful for our research,” Deuss adds.

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com Staff Writer