Earth-Sized ‘Pi Planet’ That Revolves Around Its Star Every 3.14-days – Discovered

Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com – Scientists at MIT and a group of international collaborators have discovered a “pi Earth” — an Earth-sized planet that revolves around its star every 3.14 days.

The researchers discovered signals of the planet in data taken in 2017 by the NASA Kepler Space Telescope’s K2 mission.

Scientists at MIT and elsewhere have discovered an Earth-sized planet that zips around its star every 3.14 days. Image credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle, Christine Daniloff, MIT

Scientists at MIT and elsewhere have discovered an Earth-sized planet that zips around its star every 3.14 days. Image credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle, Christine Daniloff, MIT

By zeroing in on the system earlier this year with SPECULOOS, a network of ground-based telescopes, the team confirmed that the signals were of a planet orbiting its star.

“The planet moves like clockwork,” Prajwal Niraula, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS), who is the lead author of a paper, said in a press release.

The new planet is labeled K2-315b, and it’s the 315th planetary system discovered within K2 data — just one system shy of an even more serendipitous place on the list.

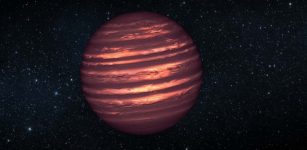

The researchers estimate that K2-315b has a radius of 0.95 that of Earth’s, making it just about Earth-sized. It orbits a cool, low-mass star that is about one-fifth the size of the sun. The planet circles its star every 3.14 days, at a blistering 81 kilometers per second, or about 181,000 miles per hour.

While its mass is yet to be determined, scientists suspect that K2-315b is terrestrial, like the Earth. But the pi planet is likely not habitable, as its tight orbit brings the planet close enough to its star to heat its surface up to 450 kelvins, or around 350 degrees Fahrenheit — perfect, as it turns out, for baking actual pie.

“This would be too hot to be habitable in the common understanding of the phrase,” says Niraula.

“We now know we can mine and extract planets from archival data, and hopefully there will be no planets left behind, especially these really important ones that have a high impact,” says Julien de Wit, who is an assistant professor in EAPS, and a member of MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

The researchers are members of SPECULOOS (The Search for habitable Planets EClipsing ULtra-cOOl Stars), which scan the sky across the southern hemisphere. Over several months in 2017, the Kepler telescope observed a part of the sky that included the cool dwarf, labeled in the K2 data as EPIC 249631677. Niraula combed through this period and found around 20 dips in the light of this star that seemed to repeat every 3.14 days.

The team analyzed the signals, testing different potential astrophysical scenarios for their origin, and confirmed that the signals were likely of a transiting planet, and not a product of some other phenomena such as a binary system of two spiraling stars. The researchers then planned to get a closer look at the star and its orbiting planet with SPECULOOS.

But first, they had to identify a window of time when they would be sure to catch a transit.

“Nailing down the best night to follow up from the ground is a little bit tricky,” says Benjamin Rackham, who developed a forecasting algorithm to predict when a transit might next occur.

“Even when you see this 3.14 day signal in the K2 data, there’s an uncertainty to that, which adds up with every orbit.”

With Rackham’s forecasting algorithm, the group narrowed in on several nights in February 2020 during which they were likely to see the planet crossing in front of its star. They then pointed SPECULOOS’ telescopes in the direction of the star and were able to see three clear transits: two with the network’s Southern Hemisphere telescopes, and the third from Artemis, in the Northern Hemisphere.

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – MessageToEagle.com Staff

![Scientific visualization of a numerical relativity simulation that describes the collision of two black holes consistent with the binary black hole merger GW170814. The simulation was done on the Theta supercomputer using the open source, numerical relativity, community software Einstein Toolkit (https://einsteintoolkit.org/). Credit: Argonne Leadership Computing Facility, Visualization and Data Analytics Group [Janet Knowles, Joseph Insley, Victor Mateevitsi, Silvio Rizzi].)](https://www.messagetoeagle.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/artifintelgrvitwaves01-307x150.jpg)