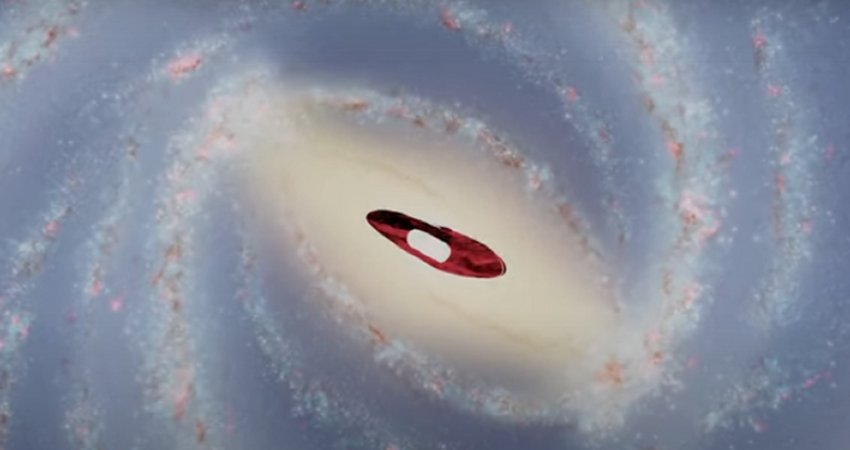

Collision Between Two Milky Way Satellite Galaxies – Confirmed

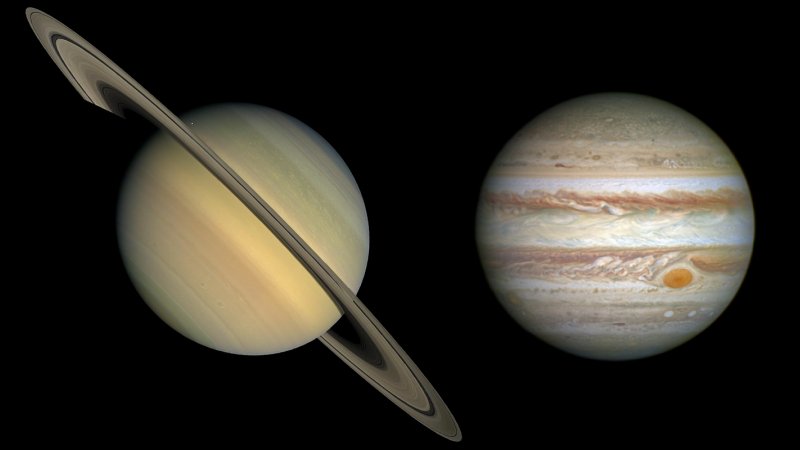

MessageToEagle.com –The Small and Large Magellanic Clouds recently collided, according to University of Michigan astronomers using a recent data release from Gaia, a new, orbiting telescope launched by the European Space Agency.

The southeast region, or “Wing,” of the Small Magellanic Cloud is moving away from the main body of that dwarf galaxy, providing the first unambiguous evidence of the collision.

“This is really one of our exciting results,” U-M professor of astronomy Sally Oey, lead author of the study, said in a press release.

“You can actually see that the Wing is its own separate region that’s moving away from the rest of the SMC.”

Together with an international team, Oey and undergraduate researcher Johnny Dorigo Jones were examining the SMC for “runaway” stars, or stars that have been ejected from clusters within the SMC.

With the help of Gaia telescope, astronomers can measure how stars move across the sky.

“We’ve been looking at very massive, hot young stars—the hottest, most luminous stars, which are fairly rare,” Oey said. “The beauty of the Small Magellanic Cloud and the Large Magellanic Cloud is that they’re their own galaxies, so we’re looking at all of the massive stars in a single galaxy.”

Examining stars in a single galaxy helps the astronomers in two ways: First, it provides a statistically complete sample of stars in one parent galaxy. Second, this gives the astronomers a uniform distance to all the stars, which helps them measure their individual velocities.

“It’s really interesting that Gaia obtained the proper motions of these stars. These motions contain everything we’re looking at,” Dorigo Jones said. “For example, if we observe someone walking in the cabin of an airplane in flight, the motion we see contains that of the plane, as well as the much slower motion of the person walking.

“So we removed the bulk motion of the entire SMC in order to learn more about the velocities of individual stars. We’re interested in the velocity of individual stars because we’re trying to understand the physical processes occurring within the cloud.”

Oey and Dorigo Jones study runaway stars to determine how they have been ejected from these clusters. In one mechanism, called the binary supernova scenario, one star in a gravitationally bound, binary pair explodes as a supernova, ejecting the other star like a slingshot. This mechanism produces X-ray-emitting binary stars.

Another mechanism is that a gravitationally unstable cluster of stars eventually ejects one or two stars from the group. This is called the dynamical ejection scenario, which produces normal binary stars. The researchers found significant numbers of runaway stars among both X-ray binaries and normal binaries, indicating that both mechanisms are important in ejecting stars from clusters.

In looking at this data, the team also observed that all the stars within the Wing—that southeast part of the SMC—are moving in a similar direction and speed. This demonstrates the SMC and LMC likely had a collision a few hundred million years ago.

MessageToEagle.com