As Earth’s Population Heads To 10 Billion, Does Anything Australians Do On Climate Change Matter?

MessageToEagle.com – As unprecedented bushfires continue to ravage the country, Prime Minister Scott Morrison and his government have been rightly criticized for their reluctance to talk about the underlying drivers of this crisis. Yet it’s not hard to see why they might be dumbstruck.

Credit: NASA

The human race has never had to grapple with a problem as large, complex or urgent as climate change.

It’s not that there aren’t solutions available. There are already some hopeful signs of an energy transition in Australia.

As Professor Ross Garnaut has explained, it would be in Australia’s economic interests to become a low-carbon energy superpower.

To successfully tackle climate change will require some painful transitions domestically, and unprecedented levels of international coordination and cooperation. But that isn’t happening.

Global action to cut emissions is falling far short of what’s needed – and meanwhile, though it’s controversial to mention, the world’s population quietly climbs ever higher.

Our growing population challenge

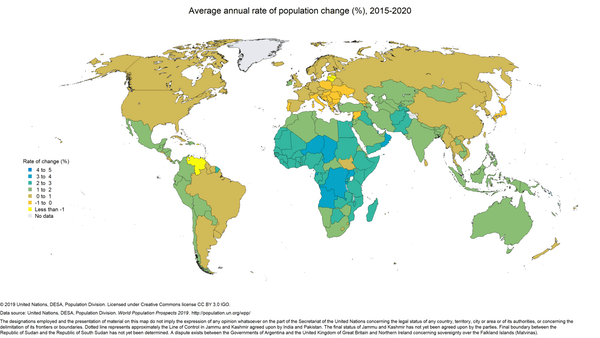

The United Nations’ World Population Prospects 2019 report forecast that by 2027, India will overtake China as the world’s most populous country.

By 2050, the UN predicts that the world’s population will be nearly 10 billion, up from 7.7 billion now. Nine countries are expected to be home to more than half of that growth: India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Indonesia, Egypt and the United States. The population of sub-Saharan Africa is expected to double by 2050 (a 99% increase), while Australia and New Zealand are expected to grow more slowly (28% increase).

Given how difficult climate politics have been here in Australia, why would we expect it to be any more politically feasible in say, India, which claims the right to develop as we did? However self-serving Australian coal supporters’ arguments about lifting Indians out of poverty are, the underlying questions of national autonomy and the ‘right’ to develop are not easily refuted.

Even talking about demography is asking for trouble – especially if it becomes caught up with questions of race, identity and the most fundamental of human rights, the right to reproduce.

While reducing population growth is plainly important in the long-term, it isn’t a quick fix for all our environmental problems. In the meantime, research has shown that supporting education for girls in poor countries is one of the single most important things we can do now to address this issue.

How Australia can show leadership

I think we need to understand that global emissions don’t have an accent, they come from many countries and we need to look at a global solution… – Prime Minister Scott Morrison on Insiders, ABC, 12 January 2020

This is the central defence of business as usual: there’s no point in Australia making huge sacrifices and ‘wrecking’ (or transforming, depending on your perspective) the economy if no one else is doing so. We contribute less than 2% to global greenhouse emissions, so – some claim – we can’t make any real difference.

As outlined in my 2019 book, Environmental Populism: The Politics of Survival in the Anthropocene, nations such as Australia can play a useful role by showing what an enlightened country, with the capacity and incentive to act, might do. If we don’t have the means and the compelling environmental reasons to make tough but meaningful policy choices, who does?

But even in the unlikely event that Australians collectively retrofitted the entire economy along sustainable lines, there would still be a lot of the world that wouldn’t, or couldn’t even if they wanted to. The development imperative really is non-negotiable in India, China and the more impoverished states of sub-Saharan Africa.

Will China lead the way?

From the privileged perspective of wealthy Australians, the ‘good’ news is that the ecological footprint of the average Ethiopian is seven times smaller than ours. India’s average is even less, despite all the recent development. However, people in India and Ethiopia may not think that’s a good thing.

One of the paradoxical impacts of globalisation is that everyone is increasingly conscious of their relative place in the international scheme of things. The legitimacy of governments – especially unelected authoritarian regimes like China’s – increasingly revolves around their capacity to deliver jobs and rising living standards. Where governments can’t deliver, the population vote with their feet.

As naturalist Sir David Attenborough warned last week, Australia’s current fires are another sign that “the moment of crisis has come”. He called on China for the global leadership we’ve been missing:

If the Chinese come and say: ‘Not because we are worried about the world but for our own reasons, we are going to take major steps to curb our carbon output […]’, everybody else would fall into line, one thinks. That would be the big change that one could hope would happen.

China has arguably already made the biggest contribution to our collective welfare with its highly contentious, now abandoned one-child policy. China’s population would have been around 400 million people larger without it, pushing us closer to the crisis Sir David fears.

To be clear, I’m not advocating compulsory population control, here or anywhere. But we do need to consider a future with billions more people, many of them aspiring to live as Australians do now.

Looking ahead, will Australians try to keep living as we do today? Or will we decide to set a new example of living well, without such a heavy ecological footprint? Resolving all these conundrums won’t be easy; perhaps not even possible. That’s another discomfiting reality that we may have to get used to.

Written by Mark Beeson – Professor of International Politics, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.