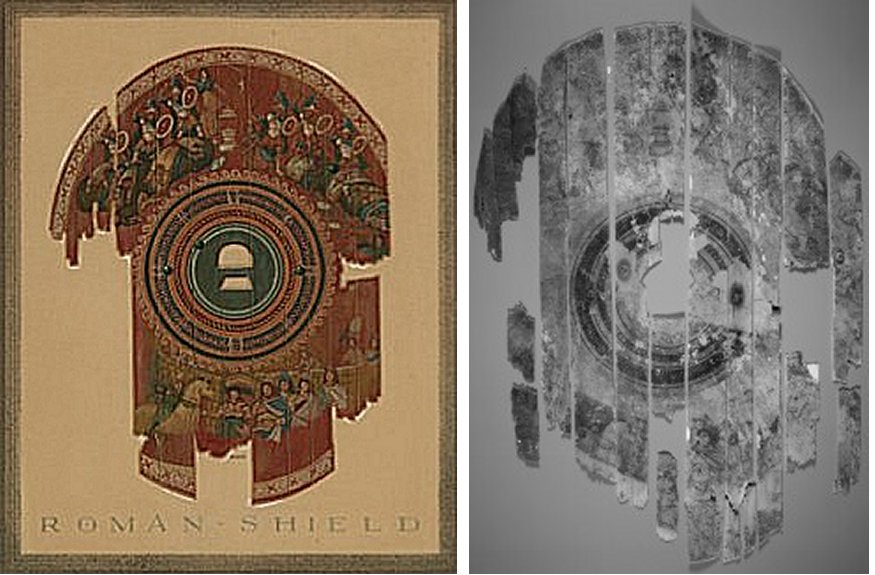

Dura-Europos Roman Shield Created With Ancient Painting Techniques On Wood

MessageToEagle.com – A Roman shield — painted with scenes from the Trojan War and possibly used in parades during ancient times – is more than 2,000 year-old artifact.

It was excavated 80 years ago but now is examined by a team of researchers at Yale University.

The shield — which dates back to the mid-third century A.D. — was discovered in 1935 by Yale archaeologists at the site of Dura-Europos, in present-day Syria and it’s one of three oval painted shields that were found at the excavation site.

The shields are in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG).

The three oval painted shields “are extraordinarily rare examples of ancient painting techniques on wood,” says Anne Gunnison, assistant conservator of objects at YUAG.

This is the first time that a comprehensive analytical study has been done on the Homeric shield, which is currently analyzed by Gunnison, Erin R. Mysak, associate conservation scientist at the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH), and Irma Passeri, associate conservator of paintings at YUAG.

One of the three shields, depicting a Roman war god figure, is on display in the Mary and James Ottaway Gallery of Ancient Dura-Europos at YUAG and was treated prior to exhibition. The third shield, which is in storage, depicts the battle of the Greeks versus the Amazons.

The Homeric shield is one of the first material characterization projects that the Technical Studies Laboratory took on.

“It was one of the first comprehensive projects that required a lot of different types of approaches — some of which we don’t have available to us on campus, so Erin has reached out to colleagues,” says Bezur.

“It’s a good example of being multidisciplinary within the conservation field. The type of analytical tools required for this study and the really sensitive characterization of organic materials required us to look outside of our laboratory. It’s a special aspect of this project that has required people who are not even here to be able to give us their input.”

Dura-Europos was founded by Macedonian Greek settlers around 300 B.C. Several different groups inhabited the region over the centuries, including Greeks, Parthians, and Romans; soldiers and civilians; and early Christian, Jewish, and pagan communities. Located on the Euphrates River, Dura-Europos was situated at the crossroads of several major trade routes. In its last historical phase, the city was a Roman military garrison, which was sacked by the Sasanians in 256 A.D. After that event, Dura-Europos was not re-inhabited.

Gunnison explains that in order to fortify the city, the Romans built up their walls, and in doing so, intentionally buried a lot of material. When the site was excavated beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, archaeologists found the shields and other material under those ramparts.

Dura-Europos, says Gunnison, “was a pristine site — because it wasn’t touched for so many years and also the soil conditions were such that the preservation of organic material was incredible.”

After excavation, a conservator and a scientist from the Harvard Art Museums studied the shields and created a conservation report that is now at Yale. The Yale team’s analysis will further illuminate which ancient painting techniques and materials were used to create the shield.

Herbert Gute, the on-site excavation artist at Dura-Europos, created illustrations of the shields. Those original watercolor illustrations, which are on display at YUAG, have guided the team in understanding what the Roman shield originally looked like.

“The drawing is remarkable,” says Passeri.

“One of the more interesting aspects of the shield — one that relates it to later works such as medieval and renaissance paintings — are the preparatory and paint layers on the piece, in which we see the use of both organic and inorganic materials,” says Passeri. “It informs us how artists or artisans developed similar technologies and approaches throughout the centuries when creating works of art.”

According to Mysak, IRR imaging is typically used to see the drawing beneath the paint of an object, but when examining the shield, it was used to view the final outlines painted onto the image. Carbon-based materials used for drawing absorb the IRR light and appear dark in the final image.

“When we first took a look at Gute’s illustration,” says Mysak, “it was hard to believe that much paint remained on the surface given how the object appears today. IRR imaging allowed us to see the figures and imagery much more clearly.

“We radiated the object with ultraviolet light to look for the visible fluorescence due to the presence of an organic red colorant, called rose madder,” continues Mysak. “The rose madder is extracted from the root of the madder plant, which is found in modern day Syria. It lights up beautifully under the UV.” The team says that the shield has an interesting combination of materials — some that are indigenous to Syria and others that would have been traded.

Gunnison says that having these three shields provides an excellent opportunity to compare them to each other but also to other ancient painted wood pieces: “There aren’t many analogous painted wood objects like these. We are able to research different techniques and compare it to the treatises from around that time. It is also interesting to study the iconography. Even though we have the watercolor and the IR, it is still fascinating to think about that in relation to that time period.”

For Mysak, one of the most significant aspects of the project has been gaining an understanding of the historical value of the shield.

“I appreciate being able to add to the understanding of the artist’s materials and technology that were available to people at that time.”

“I realized how amazing this shield is because very little painting on wood survives from antiquity,” says Gunnison. “The fact that we have three of these shields is remarkable. We keep finding things on the Trojan War shield that are pretty spectacular.”

Researchers say that it’s quite rare opportunity to study a painted object that predates early medieval paintings. I see this as an exceptional opportunity to investigate and better understand ancient Roman painting techniques.

“Though damaged, the shield retains a great deal of its imagery,” she continues. “When two conservators — specialized in different disciplines — and a scientist have the opportunity to collaborate on a project like this one, there is a great deal of dialogue and accumulated knowledge, as each of us sees things from a different perspective,” according to Mysak.

Gunnison notes that the team is still working to complete the material analysis to better guide their conservation treatment. “It is a lot of work and is very delicate. We hope to start test cleaning relatively soon and that will dictate the timeline for our conservation plans.

“I have a special love for these shields,” says Gunnison. “To some people it just looks like a pile of wood but in fact it is an archaeological artifact of great beauty. It has really blown my mind how amazing the drawing is and what skill went into the making of this object. This is one of my favorite projects I have ever worked on, and it’s definitely as a result of working with Irma and Erin and the object itself. It is really special to me.”

MessageToEagle.com via AncientPages.com

source: Yale University