Castlerigg Stone Circle: One Of Britain’s Most Important And Earliest Stone Circles

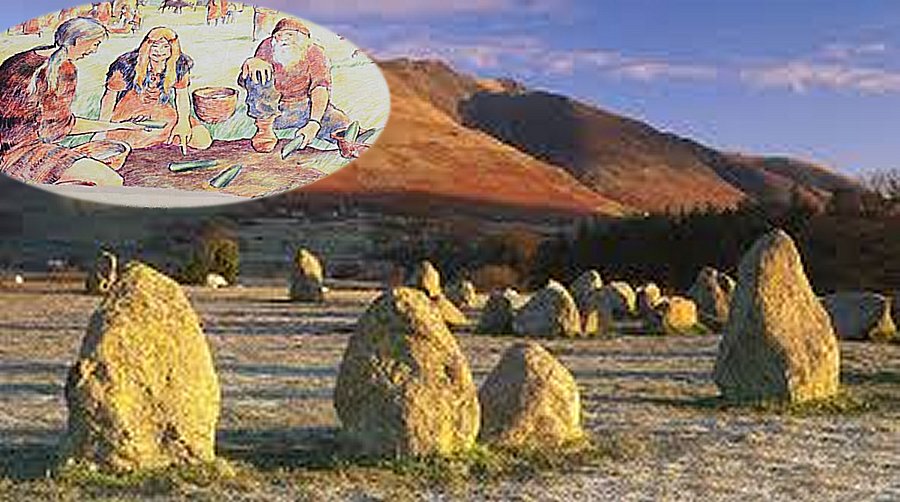

MessageToEagle.com – Prehistoric stone circles keep many secrets and fascinate ordinary people and researchers. One of the circles that has long been a puzzle, is located about 37 km (23 mi) southwest of Long Meg-Castlerigg, Keswick, Cumbria, in North West England.

It is known as the Castlerigg Stone Circle or the the Keswick Circle in the older historical sources, and its exact purpose still remains unclear, but researchers believe that it was used for ceremonial or religious purposes.

Castlerigg Stone Circle was built around 4,500 years ago in the Neolithic times.

The circle, probably once had 42 stones, now consists of 38 granite stones arranged in a circle, approximately 32.6 x 29.5 m in diameter. Within the ring is a rectangle of a further 10 standing stones. The tallest stone is 2.3 meters high. It was probably built around 3000 BC – the beginning of the later Neolithic Period.

It is one of the earliest stone circles in Britain and one of the most important, due to its geometrical and astronomical alignments as well.

It was commonly regarded as a sacred space due to its specific surroundings, in form of a rectangular space on the eastern side of the circle slightly south of the east-west axis defined by ten stones and referred to as an adytum, or sacred place in pagan temples, entered only by priests.

This rectangular stone setting, known as the ‘Sanctuary’ was most probably added later to the circle.

This extraordinary feature at Castlerigg, has not been encountered in other stone circles in the British Isles.

Including the stones along the perimeter of the circle gives a total of thirteen stones in the rectangle. Interestingly, there are three distinct gaps in the rectangle which, if they once held stones, gives 16 as the total number of stones.

For the first time, the circle is mentioned in ‘Itinerarium curiosum; or, An account of the antiquities, and remarkable curiosities in nature or art, observed in travels through Great Britain’ by William Stukeley (1687 – 1765), an Anglican clergyman and English antiquarian devoted to the archaeological research of the prehistoric monuments of Stonehenge and Avebury.

Stukeley wrote: … for a mile before we came to Keswick, on an eminence in the middle of a great concavity of those rude hills, and not far from the banks of the river Greata, I observed another Celtic work, very intire: it is 100 foot in diameter, and consists of forty stones, some very large.

At the east end of it is a grave, made of such other stones, in number about ten: this is placed in the very east point of the circle, and within it: there is not a stone wanting, though some are removed a little out of their first station: they call it the Carsles, and, corruptly I suppose, Castle-rig”.

There are still many features at Castlerigg that have to be examined; Castlerigg has not been extensively excavated to determine whether it served as a trading place or as religious center, or even both.

See also:

‘Lios na Grainsi’ – Ireland’s Largest Stone Circle

Magnificent Skellig Michael And A 1,400-Year Old Christian Monastery

Enigmatic Ale’s Stones – Sweden’s Megalithic Ship-Like Formation

It is still unknown exactly what might be preserved beneath the surface of this fascinating stone circle. Three Neolithic stone axes were found in and near the Castlerigg stone circle in 1856 and 1875 and and similar finds have been made at other Neolithic stone circles. The axes – almost never used – were often held as high status and something sacred may have been associated with them.

Megalithic stone circles were undoubtedly important meeting places for ancient people living within the scattered Neolithic communities, and the Castlerigg was one of them.

Copyright © MessageToEagle.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of MessageToEagle.com

Expand for references