Archaeological Mystery: Medieval Sword With Undeciphered Inscription Baffles Scientists

MessageToEagle.com – Scientists have been struggling with this ancient mystery for quite some time and now they need your help to decipher this enigmatic inscription written in an unknown language.

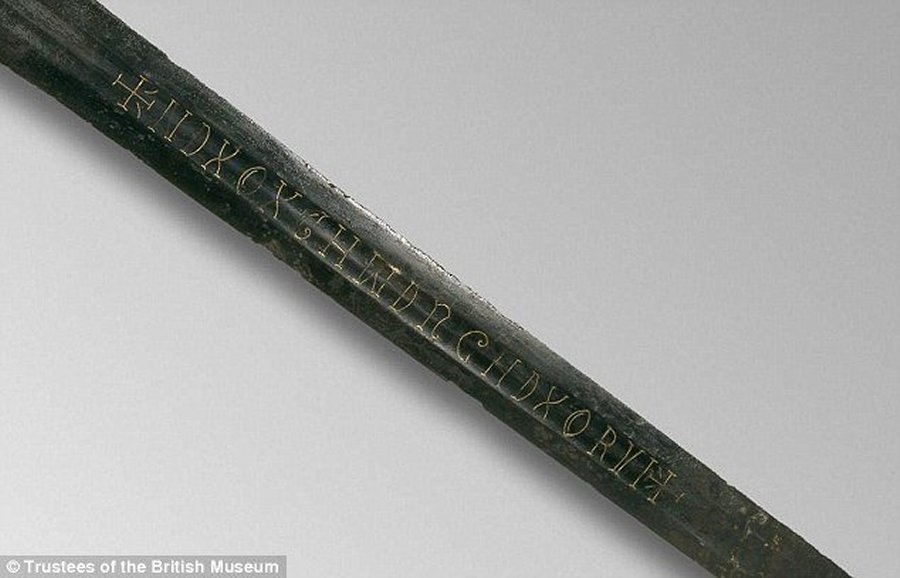

Little is known about double-edged weapon, least of all the meaning behind a cryptic 18-letter message running down the central groove which reads: NDXOXCHWDRGHDXORVI.

Now the British Library have appealed for the public’s help in cracking the conundrum.

So far it’s been suggested it may be a battle-ready phrase in medieval Welsh, the first letters from a poem or even complete gibberish fabricated by an illiterate craftsman.

The weapon was found at the bottom of the River Witham in Lincolnshire in 1825, but it’s believed the 13th century sword originally belonged to a medieval knight.

It’s typical of the type of swords medieval knights and barons would have used at the time of King John and the Magna Carta, curator Julian Harrison told MailOnline.It weighs almost 3lbs (1.2kg) and measures 38 inches (96cm) in length.‘If struck with sufficient force, it could easily have sliced a man’s head in two,’ he writes in a British Library blog.

The indecipherable inscription is inlaid with gold wire and experts have speculated the letters are a religious invocation since the language is unknown. The sword was possibly crafted in Germany, meaning it could be written in a version of that tongue. Harrison said the suggestions are coming in thick and fast and described some of them as ‘weird and wonderful’.

There’s nothing that has hit the nail on the head so far.” The variety of languages that people are speculating its written in is interesting from Sicilian to Welsh’. Janet Kennedy believes CHWDRGHD – in the middle of the inscription – is a misspelling of the German word for sword, making ORVI a name.

‘It looks like medieval Welsh: “No covering shall be over me,” possibly meaning the sword and it’s’ owner will always be ready for battle, Joe commented on the blog.’.

Harrison said this suggestion sounds plausible at first, but having studied the language, he could find no evidence to back up the suggestion.

‘For a moment you jump and think someone might have spotted something you have missed…but then, no,’ he said.

Anne Robertson reckons the letters may be the first from each line of a poem – something that’s been seen on other medieval artefacts.A number of people have picked out certain letters which had particular meanings in Latin at the time, such as ND standing for ‘nostrum dominus’ meaning our Lord, and ‘X’ for Christ. Harrison thinks this is the most probable idea so far ‘but then it gets more complicated’.

‘It’s been suggested in the past that it’s a relgious inscription and the sword may have been dropped in the river on purpose [for religious reasons] which was not uncommon,’ he explained.

There is some debate as to whether the letter looking like a ‘W’ is actually an ‘M’.A Dutch scholar is working on drawing parallels between the mysterious sword found in Lincolnshire and those on display in museums in Berlin, for example, saying there are similar inscriptions.

However ‘Ring and Raven’ believes the inscription may be badly spelt or might not mean anything at all.

‘Saxon swords in particular often had inscriptions on them that didn’t actually say anything because the people buying them (or making them) were illiterate.

‘People wanted swords with their names, or other cool inscriptions on them, and they could recognise the symbols but they couldn’t actually read.’So the blacksmiths just put any old letters on and called it a day,’ they write, likening the practice to people accidentally getting meaningless Chinese symbol tattoos.

‘I’m not optimistic we’ll ever find a definitive answer [as to what the inscription means] but it’s a lovely game to play.

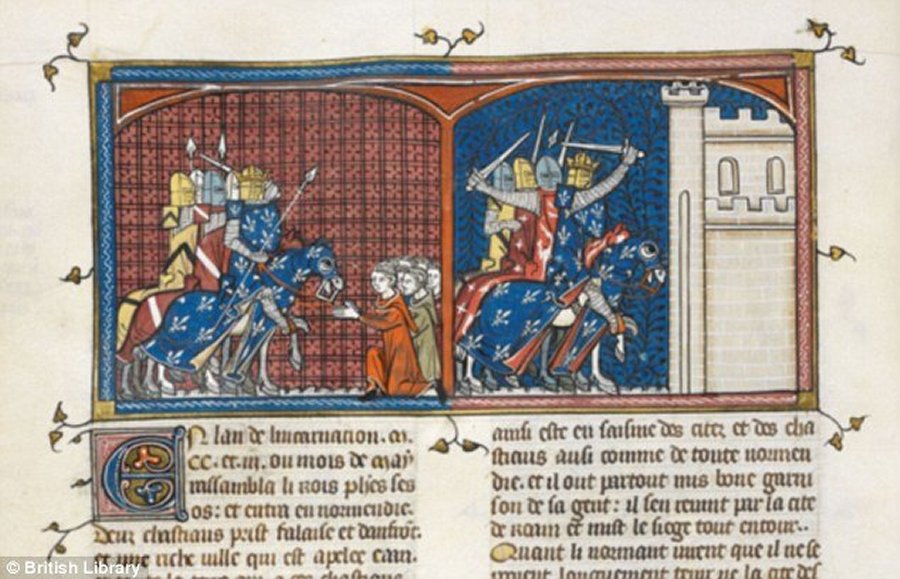

‘The sword is on display as part of the library’s exhibition Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy and is on loan from the British Museum. It’s displayed alongside a 14th-century manuscript of the Grandes chroniques de France, open at a page showing the French invasion of Normandy in 1203. The men-at-arms in that manuscript are wielding swords very similar to the one with the strange inscription, Harrison says.

MessageToEagle.com