Ancient Roman Government Structure And The Twelve Tables

MessageToEagle.com – According to an ancient legend, Rome was founded in 753 BC and the first two centuries of existence have passed under the rule of the Etruscan kings.

The decline of the monarchy dates back to 509 BC, when there was a revolt of aristocracy and the exile of the last king – Tarquinius Superbus. An important figure who contributed to this decline was, Lucius Junius Brutus, the founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of the first consuls in 509 BC.

Since that event, a new regime – ‘an aristocratic republic’ was established in Rome and the power of the Roman republic was divided among the people, the Senate and officials.

Ancient Rome’s government would not have been successful without the citizens who supported it. Ancient Romans were convinced it was their responsibility and civil duty to the empire to participate in government affairs and so they did.

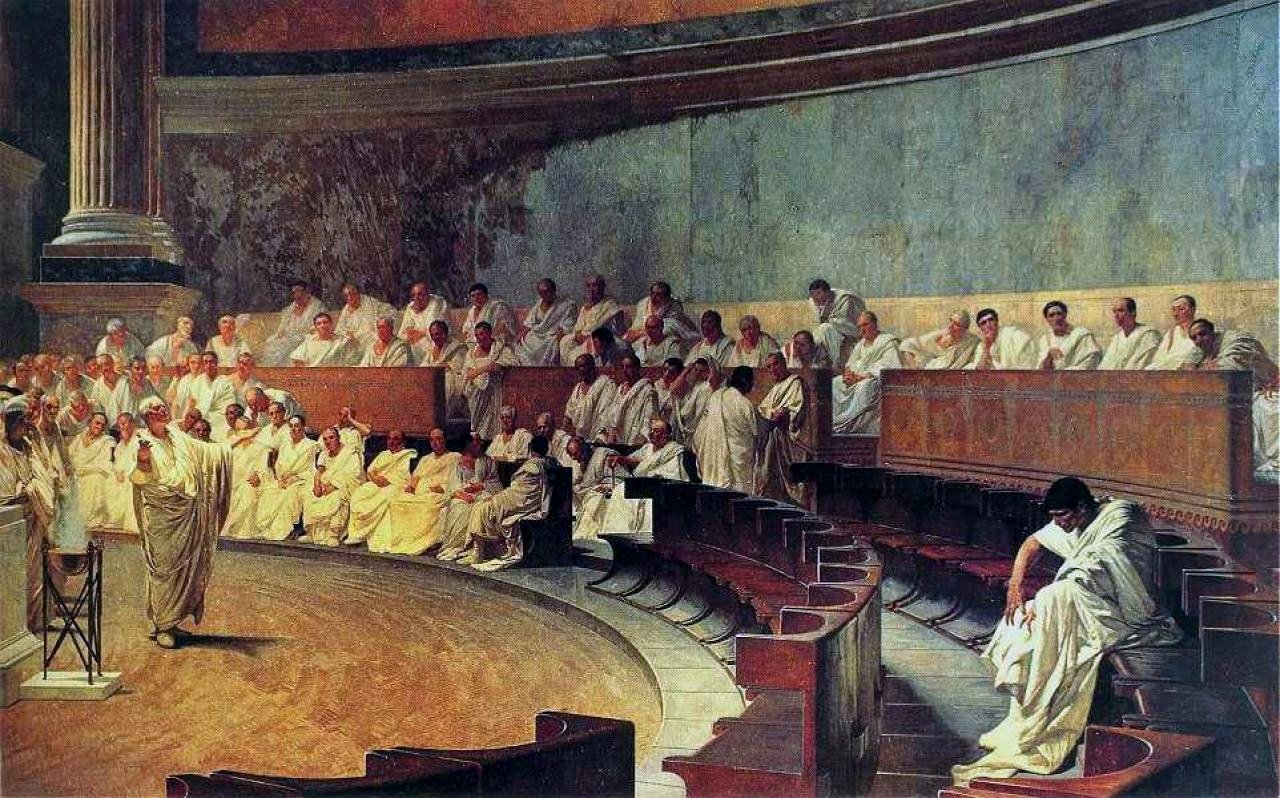

The senate was a political institution in the ancient Roman kingdom. The word senate derives from the Latin word senex, which means “old man”; the word thus means “assembly of elders”. The Roman Senate was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city (traditionally founded in 753 BC).

It survived

- the overthrow of the kings in 509 BC,

- the fall of the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC,

- the division of the Roman Empire in 395 AD,

- the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, and

- the barbarian rule of Rome in the 5th, 6th, and 7th centuries.

This was made up of leading citizens of Rome and when they met, the Senate would discuss issues such as proposed new laws, financial issues affecting Rome etc. They were usually from rich noble families and what they thought went a long way to determining Roman law.

The Senate decided on war and peace and could declare a triumph to celebrate the victorious leader and his troops or grave procession through the city.

Since the 3rd century the senate could call for the appointment of a dictator with absolute powers for a six-month period – in cases of emergency.

However, after 202, the office of dictator fell out of use. It was revived only two more times and then replaced with the “ultimate decree of the senate” which authorised the consuls to employ any means necessary to solve the crisis.

The number of senators in Rome varied much. In the earliest days of Rome traditionally under Romulus, when Rome consisted only of one tribe the senate consisted of 100 members. Later, the number of senators increased to 300 and subsequently to 600. Julius Caesar, for example, increased the senate roles to 900. With the accession of Augustus, the permanent foundation for senate numbers appears to have been fixed at 600, but this number also fluctuated throughout the empire.

Citizens of Rome would gather at an assembly to elect their own officials. The assembly could take or reject the resolution of the senate, elect the most important government officials. Almost all offices were collegial and annuals. Only office of dictator and that of censors were the exception to the rule.

Censors were officers in ancient Rome who were responsible for maintaining the census, supervising public morality, and overseeing certain aspects of the government’s finances. Censors were two and held the office for a 5-year term. If one of the censors died during his term of office, another was chosen to replace him, just as with consuls.

Consuls – the chief officials of Rome – were elected for a period of one year, by the so-called ‘People’s Assembly’ (or Plebeian Council) and there were two of them. They served together, each with veto power over the other’s actions, a normal principle for magistracies. A consul’s imperium extended over Rome, Italy, and the provinces. If a consul died during his term (not uncommon when consuls were in the forefront of battle) or was removed from office, another would be elected.

They had religious powers and were often the commanders of the army. In times of peace they had extensive executive authority. If they did not live up to expectations, they could be voted out of office at the next election. Therefore, competence was rewarded and incompetence punished.

The consuls also selected the new members of the Senate if a senator died. The consuls were often advised by a Senate about important issues, because they could not be expected to know everything.

In addition to consuls, there were other elected officials and among them – judges, magistrates and tax.

Ten “Tribunes of the People” were also elected to look after the poor of Rome.

In principle, political rights originally belonged to a social group – the patricians, a group of ruling class families.

The lower social class was represented by plebeians, but the distinction between these two groups was based purely on birth.

Their importance waned after the Struggle of the Orders (494 BC to 287 BC) and the plebeians obtained the right to appoint a special officer, representing the interests of the commoners – The Tribune of the Plebs (Tribunus plebis).

The tribune had the right to veto the actions of the consuls and other magistrates, thus protecting the interests of the plebeians as a class. Gradually, the plebeians gained access to all offices and priestly colleges.

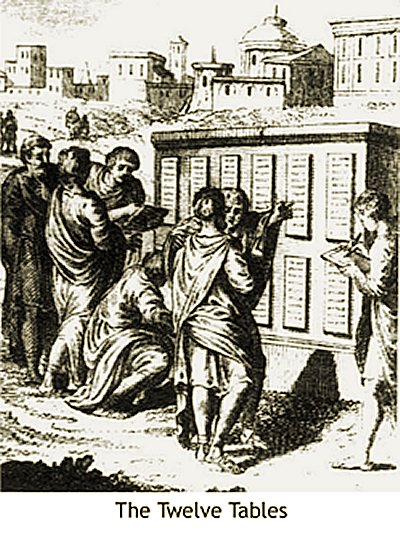

The ‘Law of the Twelve Tables’ stood at the foundation of Roman law: they were said by the Romans, to have come about as a result of the long social struggle between patricians and plebeians.

It is considered that one of the most important concessions won in this class struggle was the establishment of the Twelve Tables that guaranteed basic procedural rights for all Roman citizens as against one another.

The ‘Law of the Twelve Tables’ formed the basis of all subsequent legal systems and according to Livy, the Twelve Tables were posted publicly, so all Romans could read and know them.

Copyright © MessageToEagle.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of MessageToEagle.com