200-Million-Year-Old Flying Reptile Kuehneosaurus Discovered In Somerset, UK

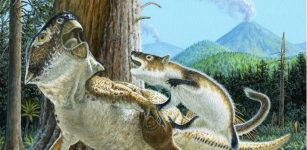

Life restoration of Kuehneosuchus and Kuehneosaurus (right). Credit: © N. Tamura – CC BY 3.0

Bones of extinct prehistoric animals are occasionally found, and they paint a picture of a world that vanished in the End-Triassic extinction.

Today, we know gliding winged reptiles called the Kuehneosaurus lived in the Mendip Hills in Somerset during the Late Triassic period.

The Kuehneosaurs were small animals, and though they resembled lizards, they were more closely related to the ancestors of crocodilians and dinosaurs. These animals were so tiny they could fit neatly on the palm of a hand, and there were two species, one with extensive wings, the other with shorter wings, made from a layer of skin stretched over their elongated side ribs, which allowed them to swoop from tree to tree.

They behaved similarly to the modern flying lizard Draco from southeast Asia. Kuehneosaurs wandered on the ground and climbed trees when looking for food. If they were suddenly surprised for unknown reasons or when they spotted a tasty insect flying by, they could launch themselves into the air and land safely 10m away.

This discovery was made by Mike Cawthorne, a student at Bristol University who is researching numerous reptile fossils from limestone quarries, which formed the biggest sub-tropical island at the time, called the Mendip Palaeo-island.

Artist’s impression of a gliding reptile Kuehneosaurus. Credit: Mike Cawthorne

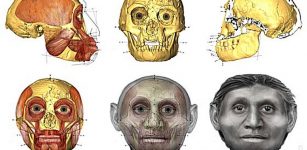

A study published in the Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association informs the area around Bristol was also home to other species of extinct reptiles. Among these was the trilophosaur Variodens, which had complex teeth, and the aquatic Pachystropheus, which probably lived a bit like a modern-day otter, likely eating shrimps and small fish.

The animals either fell or their bones were washed into caves and cracks in the limestone.

“All the beasts were small. The collections I studied had been made in the 1940s and 1950s when the quarries were still active, and palaeontologists were able to visit and see fresh rock faces and speak to the quarrymen,” Cawthorne said.

“It took a lot of work identifying the fossil bones, most of which were separate and not in a skeleton.

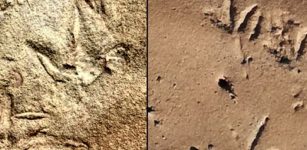

Showing partial skeleton of gliding reptile Kuehneosaurus on rock from Emborough.

Credit: David Whiteside

However, we have a lot of comparative material, and Mike Cawthorne was able to compare the isolated jaws and other bones with more complete specimens from the other sites around Bristol,” Professor Mike Benton Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences explained.

“He has shown that the Mendip Palaeo-island, which extended from Frome in the east to Weston-super-Mare in the west, nearly 30 km long, was home to diverse small reptiles feeding on the plants and insects.

He didn’t find any dinosaur bones, but it’s likely that they were there because we have found dinosaur bones in other locations of the same geological age around Bristol,” Professor Benton added.

A jawbone of unusual Triassic reptile Variodens first named from Emborough. B) Typical Emborough rock with many bones. C, D and E) bones from land-living relatives of crocodiles.

Credit: David Whiteside

“The bones were collected by some great fossil finders in the 1940s and 1950s including Tom Fry, an amateur collector working for Bristol University and who generally cycled to the quarries and returned laden with heavy bags of rocks.

The other collectors were the gifted researchers Walter Kühne, a German who was imprisoned in Great Britain in the 2nd world War, and Pamela L. Robinson from University College London. They gave their specimens to the Natural History Museum in London and the Geological collections of the University of Bristol,” Bristol’s Dr David Whiteside added.

The study was published in Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association