Ancient Human Remains In The Zagros Mountains Can Re-Write History

MessageToEagle.com – New archaeological discoveries sometimes give us reason to admit there are still many things we don’t know about our past.

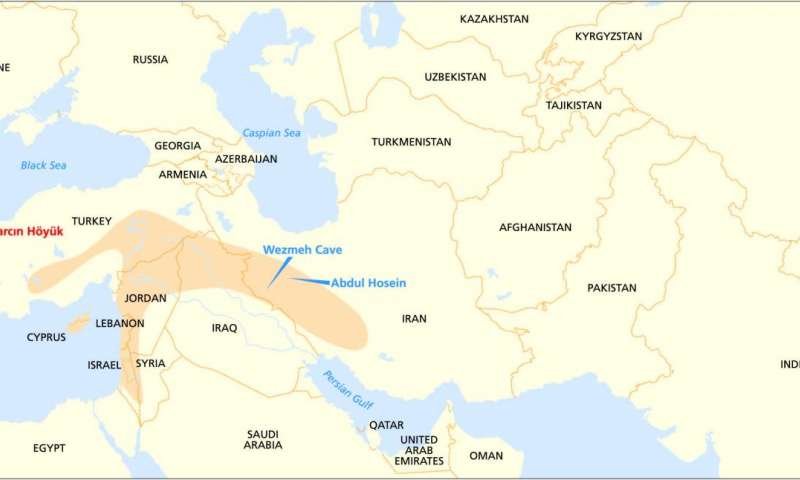

Archaeologists have discovered intriguing ancient human remains belonging to people who lived in the Zagros Mountains, the largest mountain range in Iran, Iraq and Southeastern Turkey. This find completely change our current understanding of how ancient farming spread across the world.

Scientists say they have discovered evidence of a previously unknown group of Stone Age farmers may have introduced agriculture to South Asia. The research team, consisting of scientists from Europe, the United States and Iran identified similarities between the Neolithic farmer’s DNA and that of living people from southern Asia, including from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and Iranian Zoroastrians in particular.

This new finding challenge earlier theories that attributed the spread of farming to a different population.

According to previous theories, a single group of hunter-gatherers developed agriculture in the Middle East some 10,000 years ago and then migrated to Europe, Asia and Africa, where they gradually replaced or mixed with the local population.

However, analysis of the ancient humans remains discovered in the Zagros Mountains clearly belong to a completely separate people who appear to have taken up farming around the same time as their cousins further west in Anatolia, now Turkey.

“There was this idea that there’d been one group of genius inventors who developed agriculture,” said Joachim Burger, one of the authors of the study published online Thursday in the journal Science. “Now we can see there were genetically diverse groups.”

“We know that farming technologies, including various domestic plants and animals, arose across the Fertile Crescent, with no particular centre” added co-author Professor Mark Thomas, UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment.

“But to find that this region was made up of highly genetically distinct farming populations was something of a surprise. We estimated that they separated some 46 to 77,000 years ago, so they would almost certainly have looked different, and spoken different languages. It seems like we should be talking of a federal origin of farming.”

The switch from mobile hunting and gathering to sedentary farming first occurred around 10,000 years ago in south-western Asia and was one of the most important behavioural transitions since humans first evolved in Africa some 200,000 years ago. It led to profound changes in society, including greater population densities, new diseases, poorer health, social inequality, urban living, and ultimately, the rise of ancient civilizations.

Animals and plants were first domesticated across a region stretching north from modern-day Israel, Palestine and Lebanon to Syria and eastern Turkey, then east into, northern Iraq and north-western Iran, and south into Mesopotamia; a region known as the Fertile Crescent.

“Such was the impact of farming on our species that archaeologists have debated for more than 100 years how it originated and how it was spread into neighboring regions such as Europe, North Africa and southern Asia,” said co-author Professor Stephen Shennan, UCL Institute of Archaeology.

By looking at how ancient and living people share long sections of DNA, the team showed that early farming populations were highly genetically structured, and that some of that structure was preserved as farming, and farmers, spread into neighbouring regions; Europe to the west and southern Asia to the east.

DNA examination of 9,000 to 10,000-year-old bone fragments discovered in a cave near Eslamabad, 600 kilometers (370 miles) southwest of the Iranian capital of Tehran, belonging to a man with black hair, brown eyes and dark skin, revealed the man’s diet included cereals, a sign that he had learned how to cultivate crops.

See also:

DNA Study Reveals How Europe’s Hunter-Gatherers Adapted To A New Way Of Life – Farming

Unraveling The Mystery Of The Madagascar Migration: Can Ancient Crops Solve The Riddle?

Along with three other ancient genomes from the Zagros mountains, researchers were able to piece together a picture of a population whose closest modern relatives can be found in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and among members of Iran’s Zoroastrian religious community.

The Zagros people had very different genes than modern Europeans or their crop-planting ancestors in western Anatolia and Greece, said Burger, an anthropologist and population geneticist at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany.

He said the study’s authors calculated that the two populations likely split at least 50,000 years ago, shortly after humans first ventured out of Africa.

“Early farmers from across Europe, and to some extent modern-day Europeans, can trace their DNA to early farmers living in the Aegean, whereas people living in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and India share considerably more long chunks of DNA with early farmers in Iran. This genetic legacy of early farmers persists, although of course our genetic make-up subsequently has been reshaped by many millennia of other population movements and intermixing of various groups,” Dr Garrett Hellenthal, UCL Genetics said.

These new findings could help shed light on important developments in human history that have been neglected due to researchers’ long habit of focusing on ancient migratory movements into Europe.

MessageToEagle.com